Teignmouth is the second largest town within in the Teign catchment area, with a 2009 population of 15,300. It is situated on the north bank of the mouth of the river. Historically, towns grew up at the mouth of most rivers of any size, often because the meeting of river and sea provided a site for a harbour including quays and safe anchorages, with the river itself offering a route inland. In the case of Teignmouth the unusual layout, with a shifting sand bar at the point where the river flows into the sea, made for a difficult entrance to the harbour, particularly for a vessel relying on sail – although some sailing ships would have been towed into and out of the harbour by a rowing boat..

A long thin sandbar projecting from Teignmouth beach (November 2013)

A long thin sandbar projecting from Teignmouth beach (November 2013)

The same feature as seen from the promenade.

A much more substantial sand bar opposite The Ness (May 2011) ( A sand bar of this size doesn’t appear often.)

The typical obstructions and hazards at the river mouth can be seen in this aerial photo.

But once inside the harbour small ships could anchor safely in deep water or run themselves aground on sandy beaches for survey and repair, and there was space for quays on both sides of the estuary. Inland from the harbour the wide tidal estuary is mainly mud flats at low tide, but when water transport was the predominant means of moving heavy goods, shallow draught vessels could pass up the river as far as Newton Abbot, and there were some landing and loading places along the river banks.

Apparently the shape of the sand bars is subject to patterns which go through a repeating cycle every three to five years. This was first recorded by a local seaman, Captain Thomas Spratt, in 1856, and then confirmed in 1970 by research undertaken by the Hydraulic Research Station.

The river beach (November 2007).

A new flood defence wall at the northern end of the river beach (July 2012)

Teignmouth from offshore. (August 2004)

Teignmouth is now best known as a seaside resort. It was around the 1780s when sea bathing using a ‘bathing machine’ becoming popular as a pastime for the well-to-do, and the drinking of sea water was also (mistakenly) encouraged as a cure for various ailments. The sea bathing ritual often took place before 10 o’clock in the morning, presumably because few other people were about at that time. An attendant assisted bathers to get dressed for the ordeal inside the ‘machine’, and then wheeled it into the sea so that the bather didn’t have to suffer the indignity of being seen from the shore. After dipping their customer in the water, the attendant would then winch the machine back up the beach.

People with money to spend were encouraged to build property in Teignmouth as land owners and speculators commissioned articles extolling the virtues of the town in newspapers and magazines. When Fanny Burney, the diarist and playwright, stayed in Teignmouth in 1773 she noted that the prices of provisions had doubled in the last three years due to the popularity of the town. In her journal she also described the various uses The Den (the seafront area) was put to at the time: sheep grazing, mending fishing nets, cricket matches, and pig races. By 1821 a guide to local watering places described the leisure facilities at Teignmouth, which included bathing machines, sedan chairs, donkeys and pleasure boats.

Den House, which in the 1820s was an academy for young ladies of well-to-do families, one of several in the town. (March 2012) Today it houses holiday apartments.

According to an information panel in the Teign Heritage Centre, family records show that the novelist Jane Austen came to Teignmouth in 1802 and stayed at a house called the ‘Great Bella Vista’, which may be the same building as Den House. This was of course nine years before her first book, ‘Sense and Sensibility’, was published, although by 1802 Austen had already written completed versions of several of the novels that would subsequently be so successful.

In 1815 Edward Croydon, who was in business as a printer, engraver, publisher and bookseller, set up Library and Reading Room in the building now occupied by W.H. Smiths, and in 1829 a Regatta was started – it is now claimed to be the first in England.

The Royal Library building (December 2011). As well as a circulating library, it had billiard rooms and supplies of local and London newspapers. After the railway came, Croydon was able to announce that copies of the London papers were available in the reading room on the afternoon of the day they were published. The Teignmouth Dawlish and Torquay Guide book of 1828 reports that ‘items of fancy may be purchased here, the news of the day collected and discussed, and opportunities afforded of obtaining the pleasures of social and profitable intercourse’.

Once the Napoleonic Wars were over several naval officers made their home in Teignmouth or nearby, attracted by the activities of the harbour in which many of them shared. One was Sir Edward Pellew, who bought Bitton House in 1812 when he was Commander-in-Chief of the Mediterranean Fleet. (Bitton House is now the offices of Teignmouth Town Council.) Pellew had a remarkably successful naval career and four years later was awarded the title of Viscount Exmouth, after which he became Commander-in-Chief, Plymouth, and Vice-Admiral of the United Kingdom. (He couldn’t choose to be Viscount Teignmouth because that title – or more precisely, that of Baron Teignmouth – had been awarded in 1798 to John Shore, after his six year tenure as Governor-General of India. Shore took that title because his wife was from Teignmouth, but it seems unlikely that he spent any time in the town.)

Bitton House (March 2012). According to its Heritage Listing entry this south facing frontage with eleven windows was embellished in the mid-19th century, some time after it was owned by Admiral Pellew.

Thomas Luny, already a artist of maritime subjects, moved to Teignmouth in 1807, where he received commissions from members of the local gentry and ex-mariners, including Pellew. He built himself a magnificent house (now an upmarket B&B) in Teign Street, and continued painting until his death in 1837. In his later years he was pushed around the town in a wheelchair, painting with brushes attached to his wrists. It is estimated that he produced over 3,000 works in his lifetime, over two thirds of which were produced during his time in Teignmouth – which works out at an average of one every five days for 30 years. (He must have needed the money.)

A more famous artist, J.W.M. Turner, visited Teignmouth in 1811. He was preparing sketches for a series of ‘Picturesque Views on the Southern Coast of England’. His oil painting ‘Teignmouth’, produced in 1812 from one of these sketches, is on show at Petworth House in Sussex.

When I first encountered this picture (in 2014) I wrote ‘It is a spectacular depiction of a sunset reflected off water, but could be set almost anywhere, there is nothing to associate it with Teignmouth.’ Four years later this was spotted by Ian Warrell, an expert on Turner and author of several books on his works. He got in touch because he was trying to determine the location depicted in a watercolour (now held in the Yale Center for British Art in the US) of what appears to be the same scene (probably derived from the same original sketch), but with clearer outlines of the background features than are present in the oil painting . A note in the Tate Gallery website placed it at Ringmore Strand, but Ian felt it may be a boatbuilding yard in Shaldon, because Ringmore Strand seemed too far away from Teignmouth landmarks such as St James’s church and the Ness, both of which appear in the watercolour. I realised that previously I had been misled by the ‘Teignmouth’ title and assumed that the viewpoint was looking up river from somewhere on the Teignmouth riverfront. But if it is a view down river then Ringmore Strand looks right, being the only beach at right angles to the main river channel, kept in place by a stone wall protecting a line of houses that would have been there when Turner visited in 1811. With regard to possible discrepancies in the size of the church tower and the headland, it seems reasonable to assume that Turner varied the size and position of key landscape features to add interest, rather than trying to provide a completely accurate view of the scene. Also, the Shaldon boatyards were adjoining Shaldon Green, almost directly opposite St James’s church on the opposite side of the harbour. From there the church, the fishermens’ huts on the sand spit and the Ness headland would not be in positions as depicted in the watercolour. So I need to revise my description – Turner’s painting is probably of a sunrise from the boatyard at Ringmore Strand. As such, it should really be moved to the ‘Estuary’ section of this website, but for now I’ll keep it here.

The external appearance of Den Crescent and its centrepiece, the Assembly Rooms, built in the 1820s, is relatively unchanged today. The Assembly Rooms were the hub of the town’s social life in the 19th century and lavish balls took place in the 70ft long ballroom. It was converted to an exclusive gentleman’s club in the 1870s and then to a cinema in the 1930s. The cinema closed in 2000 and it has been converted into apartments, with a pub and restaurant in the ground floor.

Den Crescent and the Assembly Rooms (March 2012)

There are some impressive surviving buildings from the 19th century in Orchard Gardens, including this terrace built in the 1890s. (October 2013)

The seafront

In contrast, the seafront has been much changed, with a paved promenade and seawall raised well above the beach to protect the Den area and surrounding buildings from storm surges, with groynes along the beach to hold the sand in place.

Teignmouth promenade and beach (September 2013)

Teignmouth promenade and beach (September 2013)

Around the turn of the 20th century a paved promenade with a low vertical sea wall had been built. But until the higher, profiled seawall was built in 1977 waves, spray and sand often used to wash over the promenade. A section of the seawall (September 2013)

A section of the seawall (September 2013)

Unfortunately the seawall did not completely protect the promenade area during the fierce storms in January and February 2014.

Several of the flowerbeds were damaged …

… and even this thick metal door in the base of the lighthouse was buckled by the force of the waves. (both February 2014)

… and even this thick metal door in the base of the lighthouse was buckled by the force of the waves. (both February 2014)

The sea wall in this area was also damaged by storms in early 2016: the access ramp and adjacent section of the wall needed repair and strengthening.

Repair work underway on the sea wall (February 2016).

The Carlton Theatre was originally built as the Den Pavilion and opened in June 1930. It was improved with the installation of tiered seating and a bar when the Teignmouth Players acquired the lease in 1986.  The Carlton Theatre (September 2013)

The Carlton Theatre (September 2013)

Never a thing of beauty, it became a bit of an eyesore in a prime location and expensive to maintain. Planning permission for a new multi-use community facility was granted in 2010, but it took a while for funding to be made available and the new building eventually opened in March 2016.

The Grand Pier, Teignmouth (September 2013).

The Grand Pier, Teignmouth (September 2013).

The pier was originally built in 1865 but suffered from structural difficulties almost immediately and had to be repaired, opening again in 1876 with a 260 foot pavilion at the shoreward end. Later a ballroom was built at the seaward end, and there was also a landing stage for excursion steamers. In the 1960s new steel piling was inserted under all the pier buildings, as many of the old wooden piles had become undermined. The ballroom closed in 1968.

Its name cannot be to distinguish it from other lesser piers in the town – it must therefore be aspirational. As well as the usual amusement arcade machines in the covered section, in the outdoor area there are some surprisingly entertaining games and rides for young children, including this ingenious weather-proof Alligator ride right at the end of the pier.

But perhaps its main attraction is the views it provides of the town and surrounding coastline. (Unfortunately both the indoor and outdoor games areas on the pier were badly damaged during the 2014 winter storms, and it isn’t clear whether they will all be repaired or replaced.)  A view of the town looking north from the pier, with the tower of St Michaels church in the centre (September 2013)

A view of the town looking north from the pier, with the tower of St Michaels church in the centre (September 2013)

The back of St Michaels is just behind the seafront at Den Promenade. This area is probably where some of the very first dwellings were built in what became East Teignmouth, by fishermen and salt workers. The church, and for that matter the whole settlement of East Teignmouth, was situated in a rather precarious position on a narrow ridge between the River Tame and the so-called Great Marsh that separated it from West Teignmouth. Before the modern seawall was built the sea used to come right up to the churchyard wall, and graves were in danger of being washed away in heavy storms. The Teign Corinthian Yacht Club building is a bit further along the promenade, from where there is a good view of the red sandstone cliffs at Hole Head. (September 2013)

The Teign Corinthian Yacht Club building is a bit further along the promenade, from where there is a good view of the red sandstone cliffs at Hole Head. (September 2013)

The cliffs at Hole Head, with the Parson and Clerk rock at the extreme right. (September 2013)

The cliffs at Hole Head, with the Parson and Clerk rock at the extreme right. (September 2013)

Since 2005 there has been an exhibition on the seafront of artworks made from waste materials, organised by Teignbridge Recycled Art In Landscape (TRAIL). One of the best pieces in 2012 was this mermaid in a wheelchair entitled ‘Swept to Earth’. It was made by a group of disabled artists from CEDA, with a creative writing group providing a backstory for the mermaid ‘Serena’ – she had been washed shore due to the changing climate, and was shocked by what humans are doing to the earth and sea. The rubbish trailing her was collected from the beach.

‘Swept to Earth’ (August 2012)

‘Swept to Earth’ (August 2012)

Also from the 2012 collection, I particularly liked ‘The Ages of Man’, a highly innovative piece by the Bishopsteignton Outdoor Art Group. The pyramid had sections depicting eight ‘Ages’ in chronological order, starting on the right hand half of the first photo (inland side): Ice, Stone, followed by those on the seaward side in the second photo (left to right): Metal, Industrial, Mass Transport, Plastic; and then on the left side of the first photo again: the Digital and Future (Dark) Ages.

Both sides of ‘The Ages of Man’ (August 2012)

Both sides of ‘The Ages of Man’ (August 2012)

The information plaque explained that the design of the Metal (Iron and Bronze) Age fuses Inca and Ancient Chinese religious masks with Man’s desire for riches, the Industrial Age is inspired by 1940s Braque cubist collages, the Mass Transport Age has shades of Art Deco travel posters, the Plastic (Bag) Age shows plastic as a double-edged benefit, and the Future (Dark) Age shows the galaxy with familiar constellations but in an unfamiliar universe. The apex of the pyramid housed a photovoltaic panel powering solar powered lights.

Then in 2015 I admired this innovative figure of a hiker with most of his body missing.

The railway

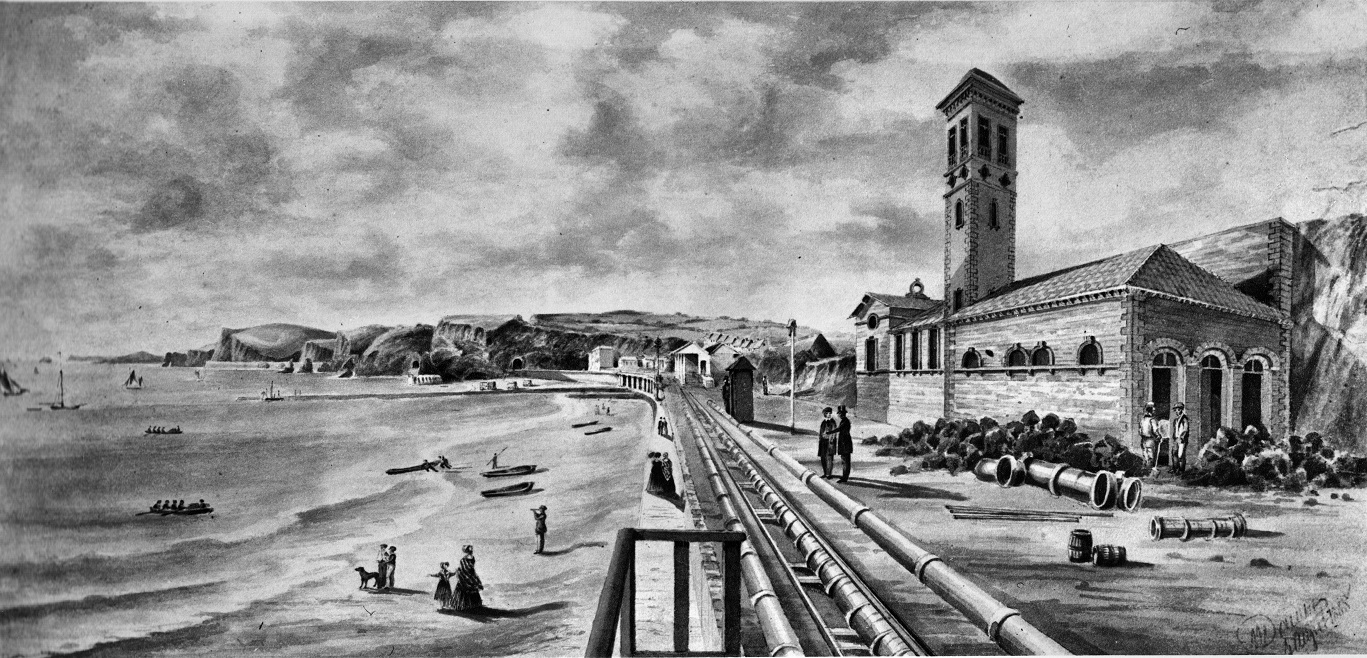

The first train arrived at Teignmouth on the 21st of May, 1846. From September 1847 an experimental atmospheric-powered service commenced on the Exeter to Newton Abbot section of the line, and it went operational the following February. Brunel had high hopes for this method of propulsion. He rented a house near the beach in Teignmouth and took an interest in the town. Because of the hilly topography inland Brunel had decided to route the line right next to the sea. One of the key design issues with atmospheric propulsion was how to seal the slot in the top of the traction pipe through which the train was connected to the piston. At the time leather was the best material available for this purpose; Vulcanised rubber would have been better, but was not yet available. Brunel underestimated the extent to which the mechanism would be soaked by sea spray. The salty water interacted with residual tannin in the leather flaps and the lime soap used to seal the leather to the traction pipe. As a result the leather rapidly deteriorated and a new approach was needed. It was decided that a combination of varnish applied to the surface of the leather and lubrication by a mixture of whale oil and seal oil would produce the necessary weather resistance and pliability of the valve. But this had the unfortunate effect of attracting rats and mice overnight when the trains were not running. If the creatures were still there when the system was started up again they could get sucked into the tube through the slot, causing the piston to jam. And the first exhausting of the propulsion tube each morning often resulted in a mixture of dead rats, mice and rusty oily water being ejected into the pumping houses, which must have been unpleasant for the engine-men. Because of these and other operational problems the atmospheric power system was discontinued in September 1848, after which conventional steam locomotives were used.

The atmospheric railway in Dawlish, showing the pumping station and the propulsion pipes.

The railway line effectively cut Teignmouth into two. To avoid undesirable gradients it needed to be more or less at sea level through the town, and therefore runs in a cutting either side of the station.Originally this section of the line was inside a tunnel but it was uncovered by 1883. Within the town the railway is now crossed by eleven bridges, the easternmost of which is the attractive Cliff Bridge, which was clearly a very expensive undertaking, yet was only built to take a footpath over the track.  Cliff Bridge (September 2013)

Cliff Bridge (September 2013)

The bridge that carries Fore Street over the railway was completely rebuilt in 2012. From its name it might be assumed that this now insignificant road used to be one of the main streets of the town, and this was indeed the case – it used to lead downhill to where there was a sheltered anchorage in the harbour, and the crossroads with Bitton Park Road (the by-passed remnant of which is now called Bitton Park Road East) was an important junction between the roads north to Exeter and west to Newton Abbot.

The junction of Fore Street (on the right) with Bitton Park Road East (on the left). (November 2013) St James’ church can just be seen behind the yew tree.

Fore Street bridge being rebuilt (March 2012)

Fore Street bridge being rebuilt (March 2012)

The rebuilt bridge is in the centre of this picture of the track just west of the station. (September 2013)

When the station was rebuilt in 1893 the Great Western Railway’s favoured motif was ‘French chateau’, which included rooflines and chimneys slightly suggestive of French Renaissance style, and some decorative ironwork on the two small flat roof areas of the frontage.  The station frontage viewed from Higher Brook St East, with a terrace of three storey houses on Glendaragh Road behind (October 2013)

The station frontage viewed from Higher Brook St East, with a terrace of three storey houses on Glendaragh Road behind (October 2013) The railway line east of Teignmouth station, from Slocum’s Bridge. (December 2011). The three churches visible along Dawlish Street are (L to R) St Michael’s, the United Reformed Church and the Catholic Church.

The railway line east of Teignmouth station, from Slocum’s Bridge. (December 2011). The three churches visible along Dawlish Street are (L to R) St Michael’s, the United Reformed Church and the Catholic Church.

The town was cut into two in an even more brutal way when the main through road was re-routed and widened in the 1960s, and several large blocks of flats built in the spaces created next to it.  The dual carriageway section of Bitton Park Road (September 2013)

The dual carriageway section of Bitton Park Road (September 2013)

The flats were presumably to partly replace the housing lost when small streets in the way of the new road were demolished. One such road to escape was Bickford Lane (one side of it, anyway), originally built as workers’ cottages around the 1860s.  Bickford Lane (September 2013)

Bickford Lane (September 2013)

Just round the corner from Bickford Lane, in Lower Brook Street, are several buildings from the early part of the 19th century, including this one with splendid bow windows.  (October 2013)

(October 2013)

The port and harbour

The port had a long history, but probably enjoyed its peak of prosperity from about 1840 to 1854. A second canal for the movement of clay down the estuary to the port, the so-called ‘Hackney Cut’ was completed in 1843, and this enabled barges to load within a short distance of the mines at Kingsteignton. In 1845 a lighthouse was erected at the entrance to the harbour.

The lighthouse seen from offshore (November 2013)

Historically the port of Teignmouth was legally administered from Exeter, which was inconvenient and tended to hinder operations. In 1852, after a long series of negotiations, the port obtained its independence from Exeter, which was cause for an elaborate celebration. This agreement still left Teignmouth having to pay duty on imports to Exeter Corporation, although Exeter declined to pay for any maintenance or improvement of the port. This was resolved the following year by a Parliamentary committee which freed Teignmouth from this obligation in exchange for a compensation payment of £3000. This sum was borrowed by the port authority, and the interest payments that had to be made on it were a cause of concern for the next 60 years.

There was also a peak in shipbuilding in the early 1850s and this generated an increase in trade for the materials needed. Railway sidings were constructed to the Old Quay in 1851, and this further stimulated trade. The main line railway was of course a faster way of getting to London than sailing up the Channel, especially when the winds were unfavourable, so some ships started stopping off at Teignmouth to drop off mail and passengers, to transfer to the railway.

In the 19th century a big proportion of the local population drew their livelihood from the port, and Teignmouth seamen went all over the world – there is evidence of this from gravestones in local churchyards – for example in the cemetery of St Nicholas, Ringmore there are graves of seamen who perished in such exotic places as Pernambuco (Brazil), Santa Anna (Gulf of Mexico) and Valparaiso (Chile) (see the Estuary webpage).

The commercial docks today, from New Quay (September 2013). A Russian vessel is drawn up at the Western Quay.

The commercial docks today, from New Quay (September 2013). A Russian vessel is drawn up at the Western Quay.

During the last 30 years of the 19th century changes in the scale of the economy and in the location of industry meant that the shortcomings of the harbour began to cause problems, and some merchants moved their business to larger ports. The last cargo of codfish from Newfoundland arrived in 1893. Minerals of various kinds moved through Teignmouth, but largely small cargoes in small ships to small ports. Lead had been the most important mineral, but the biggest local mine (Frank Mills Mine at Christow) closed in 1880. There was also some trade in imports of agricultural supplies such as fertiliser and oilcake (for animal feed) for local farmers. By the 1880s most of the shipyards in and around Teignmouth had closed, with the last merchant vessel built and owned in Teignmouth being launched in 1872. But Mansfield’s Strand Yard continued to thrive and was the largest employer in the town, as it was prepared to experiment with new types of powered ship.

The Strand today (December 2011)

The Strand today (December 2011)

Continuing north along Strand brings you to Northumberland Place, which opens out into one of the most pleasant spots in the town centre, with a mixture of buildings from different periods, including some survivors from the early 19th century.

Northumberland Place at the junction with Quay Street (September 2013).

Northumberland Place at the junction with Quay Street (September 2013).

Around the turn of the 20th century extensions to the quay were implemented. Sailing vessels were increasingly being replaced by steamers, and there was a regular monthly steamship service between Teignmouth and Liverpool carrying mixed cargoes. At this time the staple trade was in ball clay to the Staffordshire Potteries, which was shipped to Runcorn on the Mersey from where it went onwards by canal barge. The most important import was coal. There were also imports of: hides and oak for a local tannery, flints for the Bovey pottery, timber and slates for local builders. There was also some foreign trade – woodpulp from Norway and Sweden for paper production, and timber from Quebec, although this ceased once the World War started in 1914. Trade picked up again slightly in the mid-1920s, but in general, for the first forty years of the 20th century the port struggled to survive – the defects of the harbour for large ships remained, and the harbour entrance suffered from neglect, making it difficult to negotiate for the larger colliers (600 to 900 tons). Interestingly, Teignmouth was one of the few ports where sailing ships could still scrape a living in the late 1920s as they were cheaper to run than steamers, so could tolerate delays.