This section, between Dunsford and Kingsteignton, is generally known as ‘The Teign Valley’, although it is only one third of the total length of the river. This is understandable, as the countryside here resembles what most people would recognise as a classic river valley in southern England, with wooded hills either side, meadows and crop fields in the valley floor, and a road running through giving occasional glimpses of the river. ‘Teign Valley’ is used on roadsigns, and there are several enterprises using the name, including a golf club, a hotel, a children’s centre, a clay pigeon shooting business, a running club, and a bakery.

This page also covers the area in the Teign catchment to the north east of Dunsford, which is drained by two tributaries of the Teign: the Reedy Brook and the Sowton Brook.

The following paragraph from the Christow News (an on-line newsletter) of May 2006 by Tim Deane provides an interesting introduction to the area:

‘The soil of the Teign Valley will grow most things, but other places grow them more easily. That’s why the valley is nearly all pasture. The fields are steep and intricate, the ground tending to be wet and slow to warm in the spring. On the bank beside the road past Ide the blackthorn flowers two or three weeks before it does with us, and there is the difference, agriculturally speaking, between the prosperity of the Exe valley and the mere sufficiency of ours. As well as being unlikely to provide more than a modest living the Teign Valley has never been on the way to anywhere else. These two things together have enabled it to take the years quietly, mostly left in peace and little touched by the history of great events. ‘

Bridges

It seems appropriate to look first at the bridges over the main river, and the obvious starting point is Teign Bridge at Teigngrace.

Until 1827, when the first Shaldon Bridge was constructed, this bridge was the lowest crossing point on the river. If you didn’t have your own boat or access to one, the only way across the river between here and the sea would have been to walk across (carefully) at low tide at Passage House Inn on steps in the mud, or to use the Shaldon Ferry, a further four miles there and back. Accordingly, the road across the bridge used to be the main route between Exeter and Newton Abbot, but is now just a minor road.

The road over Teign Bridge (May 2009).

The road over Teign Bridge (May 2009).

When it was being rebuilt in 1815 excavations at the base of Teign Bridge indicated that at least four successive bridges had been erected at various times with or over the remains of the previous constructions. At that time it was thought that the last or upper work to create a ‘grey bridge’ was done in the sixteenth century, and before that a ‘red bridge’ had been built on the salt marsh in the thirteenth century; since which time there has been an accumulation of soil to the depth of ten feet. Prior to that there was a wooden bridge dating back to the 11th century, and there are traces of a white stone bridge possibly from the Roman period.

No traces of a Roman road have yet been discovered South of the bridge, but there can be little doubt that it continued along the line of the present Teigngrace Causeway, which forms part of the road serving the hill fort . This 300m long structure is raised slightly above the level of the surrounding fields, which are frequently flooded at this point when the river overflows its banks. It incorporates eight floodarches to enable water to flow under it. The first causeway would have been made by laying a mat of branches on the soft ground topped with rubble to form a base for a stone road surface, with larger stones used to bridge streams crossing the line of the road. It has probably been reconstructed and modified on several occasions since Roman times; the existing structure was built around 1798 and since then it has been widened, and several masonry buttresses have been built to stabilise the causeway wall. It would be normal for such a fragile structure to have a vehicle weight limit imposed, but it is used by heavily laden clay lorries from the nearby pits, and lorries carrying timber to the Teignbridge siding for onward transport by train. This has put too much strain on the shallow foundations, which in any case are set upon soft clay. As a result the walls and parapets lean outwards and cracks have appeared in the road surface. In September 2012 consent was given to install tie rods and plates and to shore up the walls along the northern end , but then further deterioration was found, and in December 2012 consent was given for similar work over a 40m stretch at the southern end. It would be great shame if the Causeway were to be damaged beyond repair before a new link road (as proposed in the 2013 Teignbridge Local Plan) is built.

Teigngrace Causeway © Derek Harper (July 2008)

Teigngrace Causeway © Derek Harper (July 2008)

Both the Teigngrace Causeway and Teign Bridge are English Heritage Grade II Listed Buildings. In its Listing notice the bridge is described as ‘local grey limestone ashlar with rusticated granite voussoirs to the arch rings, granite intrados and granite copping to the parapets. A single span with a wide segmental arch with voussoirs with chamfered rustication. Sharply-projecting stringcourse at road level which continues round the terminal piers at the ends of the abutments. A handsome road bridge with good masonry detail.’ (A voussoir is a wedge-shaped stone making up an arch, intrados is the inner curve of an arch.)

The picture below shows the remains of a previous abutment in the river bed under the bridge.

Travelling upstream from Teign Bridge, the river is crossed by a total of fifteen bridges up to the point where it turns west just south of Dunsford. In sequence south to north they are: (1) a footbridge by Sampson’s Farm, near Preston; (2) New Bridge, between clay pits at the northern end of the Bovey Basin (3) the A38 trunk road crosses the Teign south of Chudleigh Knighton; (4) a footbridge on the path between Bellmarsh Barton and Chudleigh Knighton; (5) a road bridge carrying the B3193 over the river just north of the A38; (6) Chudleigh Bridge, on the old main road between Plymouth and Exeter; (7) Huxbear Bridge, a railway bridge of girder construction on the now dismantled Teign Valley Railway; (8) Crockham Bridge, another disused railway bridge; (9) Crocombe Bridge, built in 1836, on the minor road between Trusham and Hennock; (10) Whetcombe Bridge, leading only to Whetcombe Barton; (11) Spara Bridge, built in 1660, just by Lower Ashton; (12) Christow Bridge, situated by the Teign House pub and the disused Christow railway station; (13) a footbridge slightly upstream from Christow Bridge, within the old railway station; (14) Bridford Bridge, probably built in the 16th century and, like many other ancient bridges, widened sometime in the 19th century – described by the authors of ‘Old Devon Bridges’ as the ‘most interesting bridge over the River Teign’; and (15) Sowton Cottage Bridge.

The river near Sampson’s Farm, between Teignbridge and Preston (March 2012)

The river near Sampson’s Farm, between Teignbridge and Preston (March 2012)

The footbridge over the Teign at Sampson’s Farm (March 2012)

The footbridge over the Teign at Sampson’s Farm (March 2012)

The river near Ventiford, a little upstream from the previous photo (October 2016). This shows the impressive depth of river silt that has been deposited in this part of the flood plain.

The river near Ventiford, a little upstream from the previous photo (October 2016). This shows the impressive depth of river silt that has been deposited in this part of the flood plain.

Crockham railway bridge – disused and overgrown. (September 2009)

Crockham railway bridge – disused and overgrown. (September 2009)

The river just downstream from Crocombe Bridge (September 2009)

The river just downstream from Crocombe Bridge (September 2009)

Whetcombe Bridge (November 2012). The sign on the left is for Tinkley Koi Farm, on the site of a former stone quarry, the main feature of which is a one acre lake formed by infiltration from the nearby river into the old quarry workings since it was closed in 1931. The lake is now eighty feet deep and stocked with over 300 koi carp for sale – an innovative use for an otherwise useless hole in the ground.

Whetcombe Bridge (November 2012). The sign on the left is for Tinkley Koi Farm, on the site of a former stone quarry, the main feature of which is a one acre lake formed by infiltration from the nearby river into the old quarry workings since it was closed in 1931. The lake is now eighty feet deep and stocked with over 300 koi carp for sale – an innovative use for an otherwise useless hole in the ground.

Spara Bridge, showing the impressive triangular refuges, which continue downwards as cutwaters. (October 2009)

Spara Bridge, showing the impressive triangular refuges, which continue downwards as cutwaters. (October 2009)

Another view of this beautiful little bridge (October 2013)

Another view of this beautiful little bridge (October 2013)

Christow Bridge, with the old station buildings in the middle distance. (September 2009). This bridge was built in 1914, although the railings are clearly much more recent. It replaced the original road crossing, which is now a footbridge, located slightly upstream.

Christow Bridge, with the old station buildings in the middle distance. (September 2009). This bridge was built in 1914, although the railings are clearly much more recent. It replaced the original road crossing, which is now a footbridge, located slightly upstream.

The parapet of Bridford Bridge (October 2009). Apart from its 16th century origins, presumably another reason why this bridge was judged particularly interesting is its curved form, needed because it is situated on a bend in the road – although why the road has to bend at this point is not clear.

The parapet of Bridford Bridge (October 2009). Apart from its 16th century origins, presumably another reason why this bridge was judged particularly interesting is its curved form, needed because it is situated on a bend in the road – although why the road has to bend at this point is not clear.

Sowton Cottage Bridge (October 2013) Unlike most other bridges in this series, this one carries a road with a fair volume of traffic (the B3193) over the river, but it is still very humped and narrow, only allowing one vehicle at a time.

Sowton Cottage Bridge (October 2013) Unlike most other bridges in this series, this one carries a road with a fair volume of traffic (the B3193) over the river, but it is still very humped and narrow, only allowing one vehicle at a time.

About a mile upstream from Sowton Cott Bridge, a footpath from Dunsford to Bridford crosses the river via these stepping stones. (October 2013) The river can also be forded at this point when the water level is low.

For hundreds of years all the small villages in this area, including Bridford, Christow, Ashton and Dunsford, used to have their annual fair. For residents whose life was largely dictated by the annual farming cycle and who saw very little of the world beyond their immediate surroundings, this was something to look forward to all year. There would be dancing on the village green, entertainers (like singers, acrobats, and jesters) fairground games, archery and boxing tournaments, stalls of fancy things to buy, and much cider to drink.

An illustration of a horse-powered merry-go-round at a village fair c1810 by W H Payne (from http://islesproject.wordpress.com)

An illustration of a horse-powered merry-go-round at a village fair c1810 by W H Payne (from http://islesproject.wordpress.com)

For better or worse, this began to change with the arrival of the railway and gradually improving road transport. By the turn of the 20th century, the village fairs were gone, or were much reduced in size and soon to discontinue. By then villagers were able regularly to visit the local town (Newton Abbot or Exeter) on the railway or by coach on the improved roads, to go to the market or the horse racing, and to visit the shops.

A horse drawn coach fully loaded for a works outing, around 1900 © Paul Townsend

A horse drawn coach fully loaded for a works outing, around 1900 © Paul Townsend

In looking at the villages in the valley, we’ll start on the western side, where there are three: Christow, Bridford and Hennock.

Christow

Christow is a large village situated on high ground well up above the valley floor. This view is from the eastern side of the valley. From here the steep rise from the river to the village is not apparent.

The Teign valley with Christow in the middle distance. (March 2013)

The Teign valley with Christow in the middle distance. (March 2013)

It is set in farming country, but only one working farm remains in the village itself, out of the dozen or more that existed in the parish before the consolidations and changes in agricultural practices that took place during the 20th century. Thus in the area there are several old farmhouses dating from the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries – two of the best examples being New House Farm close to the church, and Pale Farm in Dry Lane.

New House Farm, in the centre of the village close to the church. (November 2012)

New House Farm, in the centre of the village close to the church. (November 2012)

Pale Farmhouse, described in the Listed Buildings register as of ‘late medieval origins, remodelled in the late 16th/ early 17th century in two phases, with the barn at right end converted to domestic use in the late 20th century’. Also ‘Pale Farmhouse is said to have been the home of the Archer family since the 12th century.’

Pale Farmhouse, described in the Listed Buildings register as of ‘late medieval origins, remodelled in the late 16th/ early 17th century in two phases, with the barn at right end converted to domestic use in the late 20th century’. Also ‘Pale Farmhouse is said to have been the home of the Archer family since the 12th century.’

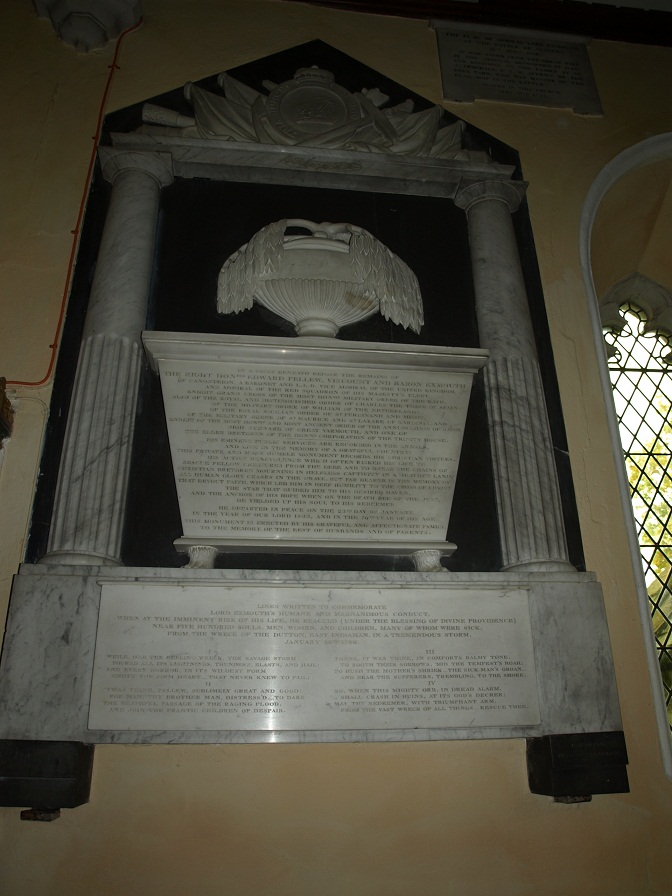

The village church (November 2012), dedicated to St James, (but probably originally St Christina, from which the modern place name is derived) was built in the 15th century. Its granite tower, which bears the date 1630, when it was either rebuilt in its old form or substantially repaired, is one of the finest in Devon. Inside there is a Norman font, a highly coloured 15th century wooden screen, and a monument to Edward Pellew, Viscount Exmouth, who died in 1838.

The village church (November 2012), dedicated to St James, (but probably originally St Christina, from which the modern place name is derived) was built in the 15th century. Its granite tower, which bears the date 1630, when it was either rebuilt in its old form or substantially repaired, is one of the finest in Devon. Inside there is a Norman font, a highly coloured 15th century wooden screen, and a monument to Edward Pellew, Viscount Exmouth, who died in 1838.

The white marble memorial to Edward, Viscount Exmouth, who died in 1838. It comprises a sarcophagus, urn and laurels framed by half -columns, naval trophies above and long verse on a separate tablet below celebrating Pellew’s rescue of 500 people from the wreck of East Indiaman the ‘Dutton’ in 1796. For many years after his death the flag flown by the gallant Admiral at the battle of Algiers in 1816 (his most notable triumph) hung above the monument.

The white marble memorial to Edward, Viscount Exmouth, who died in 1838. It comprises a sarcophagus, urn and laurels framed by half -columns, naval trophies above and long verse on a separate tablet below celebrating Pellew’s rescue of 500 people from the wreck of East Indiaman the ‘Dutton’ in 1796. For many years after his death the flag flown by the gallant Admiral at the battle of Algiers in 1816 (his most notable triumph) hung above the monument.

There are three reservoirs situated on a relatively high plateau west of Christow. Tottiford and Trenchford reservoirs are linked; the former was built in 1861 and expanded in 1865, the latter was built in 1907 and is notable for offering pike fishing – the largest caught was in 2005 at 27lb 4oz. Kennick was built in 1884 and supplies Torquay with water; it is a top rated rainbow trout fishery, with angling from the banks and boats.

In 2010 there was a (Channel 4) Time Team excavation on the bed of Tottiford reservoir, carried out when it was drained for maintenance purposes. The archaeologists made some significant finds and concluded that the site was a ceremonial or meeting place throughout the Mesolithic period (from roughly 6500BC) perhaps because the surrounding landscape (now buried under the reservoir water) formed a natural bowl with streams and two small islands. Then somewhere between 3000 and 2000BC the site was considered important enough for a double stone row and a stone circle to be added.

Trenchford Reservoir (November 2012)

Trenchford Reservoir (November 2012)

Blackingstone Rock (November 2012)

Blackingstone Rock (November 2012)

This granite outcrop is about a mile north west of Kennick Reservoir. There used to be a quarry about three quarters of a mile north west of it, and in the early part of the last century it was this mine that supplied the stone for the building of Castle Drogo. This might have been the nearest granite quarry to the site, but it is still at least eight miles away. The stone blocks were transported to the site for the first few years at least on horse drawn wagons, which would have had to cross Mardon Down, on past Butterdown Hill and the ancient earthworks of Cranbrook Castle, and then negotiate the steep hill down into the river valley and up the other side to the building site itself on a crag overlooking the Teign gorge. This sounds really arduous, although I suppose before motor transport became widely available, hauliers would have been used to such journeys.

The northern side of Blackingstone Rock (February 2016). In this winter light it has quite a brooding presence!

A bit further on, on the extreme north west edge of the area covered in this section, this is Cossick Cross, on the B3212 between Moretonhampstead and Doccombe (November 2012)

A bit further on, on the extreme north west edge of the area covered in this section, this is Cossick Cross, on the B3212 between Moretonhampstead and Doccombe (November 2012)

Doccombe is a small village on the B3212 from Moretonhampstead to Steps Bridge. It has some good looking buildings but clearly not much happens here now. Like so many small villages, within living memory it has had a post office, a pub, a shop and some working farms. The post office closed, the pub was and the farmhouses have largely been bought up by non-farming residents; the fields being sold off or rented out for grazing.

Manor Cottage, Doccombe (February 2016)

Bridford

Bridford is situated 700 feet above sea level, a long way uphill from the bottom of the valley, especially before the arrival of the internal combustion engine. So prior to the 20th century it was pretty isolated and its communications with the outside world were limited – for example, it is reported that in 1820 it took six weeks for the death of King George III to reach the village.

The 17th century Bridford Inn, which also incorporates the village shop (November 2012)

The 17th century Bridford Inn, which also incorporates the village shop (November 2012)

Even today it is not the easiest place to reach, being served only by steep minor roads, like this one, which runs between Bridford and Christow, and here right beside the quaintly named Rookery Brook. (November 2012)

The interior of St Thomas a Becket, Bridford (November 2012), showing the unusual keeled boarded wagon roof. Most of the structure is from the 15th century, apart from the chancel (the area around the altar) which is thought to be earlier. Inside there is a gorgeous early 16th century carved and painted wooden rood screen with eight bays, which continues around the pulpit.

The interior of St Thomas a Becket, Bridford (November 2012), showing the unusual keeled boarded wagon roof. Most of the structure is from the 15th century, apart from the chancel (the area around the altar) which is thought to be earlier. Inside there is a gorgeous early 16th century carved and painted wooden rood screen with eight bays, which continues around the pulpit.

The figures on the lower (dado) part of the screen are a little hard to interpret, but may represent both churchmen and a variety of other occupations including what could be a scribe, a jailor, a juggler, and an acrobat. As usual, the faces have been mutilated, almost certainly during the Civil War.

Detail of the rood screen and front of the pulpit.

Detail of the rood screen and front of the pulpit.

The upper part of the screen features elaborate carvings that include the Tudor Rose and pomegranates, the symbol of Katharine of Aragon, who was married to King Henry VIII when the screen is thought to have been created.

On the back of the dado panels there are various half-figures painted in grisaille – a method of painting in grey monochrome that is designed to represent objects in relief. The church guidebook says that ‘these 16th century figures are naively, though robustly, painted. They provide an excellent observation of the costume of the period.’

One of the figures on the back of the rood screen: some flesh colouring has been added to faces and hands. They had been overpainted, but were restored in recent times.

There are fine views from the village eastward to Haldon. About a mile to the west of the village is Heltor Rock which, at over 1,000 feet, provides an even better vantage point.

Heltor Rock (February 2016)

Hennock

Hennock is a small village set 600 ft above sea level on a granite shelf above the Teign valley.

Church Road, Hennock (November 2012)

Church Road, Hennock (November 2012)

The churchyard of St Mary The Virgin, Hennock, with views across the Teign valley to the Haldon Hills beyond. (November 2012)

The churchyard of St Mary The Virgin, Hennock, with views across the Teign valley to the Haldon Hills beyond. (November 2012)

The Palk Arms public house, Hennock (November 2012). Hennock was once owned by the wealthy Palk family, and the pub is possibly sited on what was, a very long time ago, the village green. There used to be a cider bar next door – the Union Inn In Devon cider was always plentiful, being made from local orchards. (The house next to the Palk Arms is now called Union Cottage.)

The Palk Arms public house, Hennock (November 2012). Hennock was once owned by the wealthy Palk family, and the pub is possibly sited on what was, a very long time ago, the village green. There used to be a cider bar next door – the Union Inn In Devon cider was always plentiful, being made from local orchards. (The house next to the Palk Arms is now called Union Cottage.)

The Palk family came to prominence because of Robert Palk (1707- 1798) and his immensely lucrative activities as a director of the East India Company, and then as Governor of Madras. (The sea channel between India and Sri Lanka is named after him – the Palk Strait.) He returned to England in 1767 after which, among other things, he conducted a lengthy correspondence with Warren Hastings, the first Governor General of India, much of which is now in a British Museum collection. He also purchased land around what is now Torquay harbour, which he intended to develop – at that time Torquay was just a small fishing village. However, his Manor House overlooked a piece of land owned by a family who refused to sell it, so he decided to move somewhere else. He bought Haldon House, which had been modelled on Buckingham House in London (now Buckingham Palace), was convenient for Torquay and Exeter, and came with a great deal of land. Some of this building has survived as part of the Lord Haldon Hotel. Later the Palk estates were expanded and at one time included Hennock, Trusham, Chudleigh, Christow, Dunsford, Dunchideock, Doddiscombsleigh, Bridford, Ide, Kenn, Kennford, Alphington, Exminster, Week, Sowton, , Shillingford, and some parts of Powderham. Haldon Belvedere (originally Lawrence Castle) which was built by Robert Palk as a tribute to his friend General Stringer Lawrence, is probably the most prominent reminder of the Palks; the tower on the Haldon Hills being visible for miles around.

Haldon Belvedere is prominent on the skyline in this slightly incongruous scene of llamas grazing at Lakeham Farm, near Doddiscombsleigh (April 2013)

Haldon Belvedere is prominent on the skyline in this slightly incongruous scene of llamas grazing at Lakeham Farm, near Doddiscombsleigh (April 2013)

The Palks remained significant landowners in Torquay. Robert Palk’s son, Lawrence, commissioned the building of a new harbour, but later had to flee to France to avoid his debtors, and much of the building and basic infrastructure of central Torquay was initiated by his solicitor, William Kitson, who had sole charge of the Palk estates from 1833. Notable developments by the Palk estates were Hesketh Crescent (1848), the Imperial Hotel (1866), and a new yacht harbour (1870).

Unfortunately, later generations were unable to remain solvent and the family were bankrupt by the late 1800s, resulting in a series of sales of their possessions, including a very impressive art collection, started by Robert Palk and augmented by later family portraits by leading artists of the day.

Possibly the best known painting in the Palk collection was ‘A Scene on the Ice near Dordrecht’ (1642) by Jan van Goyen, which made 380 guineas at auction. It was sold to, and is still in the collection of, the National Gallery. There is much more information on the Palks at http://palkfamily.info/5001.html, by Iain Fraser.  (c) National Gallery, London

(c) National Gallery, London

Teign Village is a hamlet of fifty-five houses built either side of the lane that leads uphill to Hennock from the main road through the valley. The majority of the houses were built in 1910 by the Teign Valley Granite Company to provide accommodation for workers at the local quarry. All the house bricks were made by the company, and originally the brickwork was on display as the walls were not rendered, as they are now.

Teign Village (November 2012) The large building on the left is the Sports and Social Club, which was founded in 1913 by the local quarry manager, and is still going strong.

Teign Village (November 2012) The large building on the left is the Sports and Social Club, which was founded in 1913 by the local quarry manager, and is still going strong.

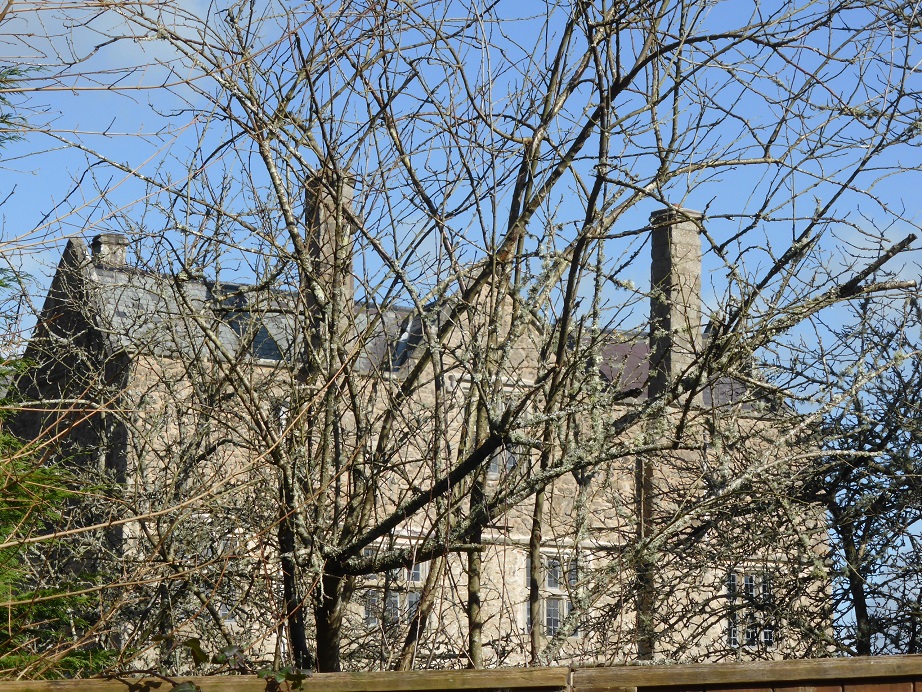

The locality of Canonteign is situated between Christow and Hennock. The manor of Canonteign was owned by the Black Canons of Merton in Surrey (hence the name), to whom it was conveyed around 1268 by the abbot and convent of St Mary du Val in Normandy – they had been given it in about 1125. After the dissolution of the monasteries in 1540 the manor ended up in the ownership of the Davy family who built the magnificent Canonteign Barton manor house in the late 16th century.

Canonteign Manor: from the road the building is completely obscured by trees: this is the best view available, when the trees are still bare (February 2016).

The house saw much action during the Civil War: it was considered a potentially strong fortress and was garrisoned for the King. However, it was attacked and taken by Sir John Fairfax in 1645. In 1820 the manors of Canonteign and Christow were purchased by Sir Edward Pellew, later Viscount Exmouth (see Teignmouth chapter). The 16th century manor house was reduced to a farm and he had a new house built close by in 1828 in the Greek Revival style. The manor house was semi-derelict prior to a complete restoration and re-modelling from the 1970s, such that the original layout can now no longer be determined. It was recently (2011) on sale for £3,250,000. The 1820s house is now a venue for wedding receptions.

Not far away is the engine house at Wheal Exmouth lead and barytes mine, which operated from the 1850s to 1880. Before being screened by tree planting it was visible from Canonteign House, hence its unusually ornamental style, designed to match the adjacent octagonal ventilation shaft.

The engine house during renovation in February 2016.

Canonteign Falls are reputed to be the highest in England, with a sheer drop of 70 metres. When the Wheal Exmouth lead and silver mine was in operation the falls were diverted into a leat to drive a wheel to power the mining operations. When the mine closed around 1880 the then Lady Exmouth employed some of the redundant miners to divert the water over the high outcrop of rocks as a part of starting the landscaping of the estate.

A section of Canonteign Falls (February 2016)

Chudleigh Knighton, situated on the northern edge of the Bovey Basin next to the Teign just above its confluence with the Bovey, has ancient origins – it is mentioned in the Domesday Book as ‘Chenistona’. It has strong historical associations with the ball clay mining industry and with brick and tile making, and until 1973 was on the main A38 road from Exeter to Plymouth. Nowadays it appears to be a rather characterless place.

The church of St Paul, built in 1841-42, has an unusual cruciform shape and is faced with Haldon flint. (January 2013)

The church of St Paul, built in 1841-42, has an unusual cruciform shape and is faced with Haldon flint. (January 2013)

The oldest building in the village is probably the Claycutters Arms, originally a row of cottages, made of roughcast cob and stone with a thatched roof, which dates from the second half of the 16th century or very early 17th century.

The Claycutters Arms public house, Chudleigh Knighton (May, 2013)

The Claycutters Arms public house, Chudleigh Knighton (May, 2013)

South of Chudleigh Knighton and the A38, a hilly area separates the Bovey Basin from the valley of the Lemon. The picture below was taken near Higher Staplehill Farm, and is typical of scenery in the lower Teign valley – grazing land in the foreground, with distant views of clay pits and the Haldon Hills beyond. (May 2012)

Chudleigh

Conduit Square, Chudleigh, looking up Old Exeter Road. (September 2009)

Conduit Square, Chudleigh, looking up Old Exeter Road. (September 2009)

Chudleigh is situated on high ground on the east bank of the Teign, on a rounded spur projecting from the south-west side of the Haldon Hills. A broad valley to the south-east of the town has been formed by the Kate Brook, a tributary of the Teign whose source is on the Haldon Hills to the northeast.

Clifford Bridge, over the Kate Brook (April 2013)

Clifford Bridge, over the Kate Brook (April 2013)

The town is of Saxon origin, with the initial settlement probably clustered around the site of the church. It belonged to the Church (actually to the Bishop of Exeter), probably from the 10th century, when King Athelstan founded an abbey church at Exeter and endowed it with substantial landholdings, until the Reformation.

The Bishop’s Palace was originally built soon after the Norman Conquest, in about 1080, for the splendidly named Osbern Fitz-Osbern, the then Bishop of Exeter. It would have been used for official business, as a rural retreat and as a convenient stopping place when the bishop and his entourage was travelling around the area. In 1100 the bishop was very influential and ruled over a vast territory stretching from Somerset to west Cornwall.

The only substantial remains of the Bishop’s Palace, in a grazing field of Palace Farm, in Rock Road. (October 2013)

The only substantial remains of the Bishop’s Palace, in a grazing field of Palace Farm, in Rock Road. (October 2013)

There are no records of what the palace was like, and no doubt it would have changed hugely in the 450 years of its existence. It is recorded that the best known bishop of Exeter in the medieval period, John Grandisson (1327-1369), stayed at Chudleigh during the Black Plague (1348-9) when living in towns was dangerous, and subsequently spent the last twenty years of his life at his Chudleigh residence. By the 1520s it was in a state of disrepair as the then bishop was involved with national events and spent very little time in Exeter or the surrounding area. All lands and residences of the See of Exeter were confiscated in 1546; Chudleigh was transferred to private ownership.

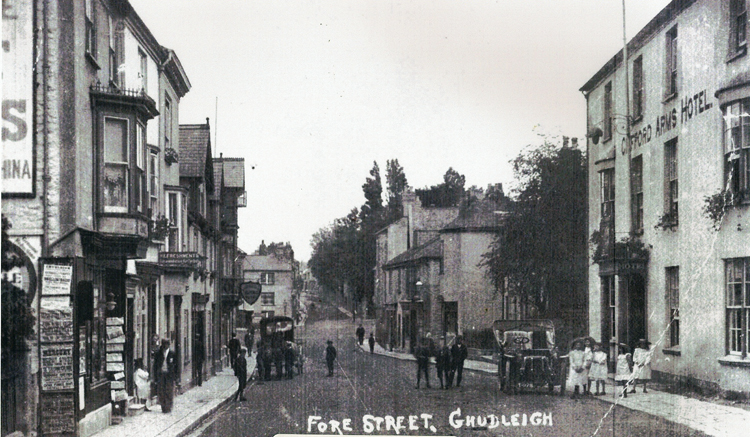

Under Church ownership Chudleigh became a prosperous market town, and in 1309 it was granted a charter to hold a weekly market and an annual fair. It was heavily involved with wool: local farmers and land owners became wealthy through sheep rearing, and generations of townsfolk gained employment from the washing, combing, spinning and weaving of wool. Indeed, Chudleigh produced some of the finest fabrics in Devon, which were known as ‘Chudleighs’. The wool processing business came to an end towards the end of the 18th century when steam-driven mills came into operation in Yorkshire and elsewhere, and it became increasingly dependent on the coaching trade. Its location on the main Plymouth to Exeter road generated business for blacksmiths, wheelwrights, saddlers, innkeepers and others, until the 19th century when the railway arrived; the last mail coach through the town coincided with the railway coming to Newton Abbot in 1846. The advent of the automobile meant that traffic of a different kind increased through the town during the 20th century, but most of that traffic didn’t stop and was therefore a nuisance rather than a source of business to the townspeople. In particular, in the 1950s and 1960s the town suffered severe disruption on summer weekends from holiday traffic. In 1973 the through traffic was diverted onto the new A38, and the roads in the town became quiet again. Over the past forty years the population has doubled and Chudleigh is now a very desirable place to live, in some measure due to the ready access provided by the A38 to Exeter, Torbay, Plymouth, and to the M5.

In May 1807 the greatest disaster in Chudleigh’s history saw two thirds of the town burned down and 1200 people made homeless. It started in a baker’s house and spread quickly via burning embers blowing in the wind onto adjacent properties, especially onto the thatched roofs of stables and out buildings. At one point a barrel of gunpowder, which had been forgotten in a storeroom, blew up, creating general alarm and scattering objects all over the town. The only fire-engine was soon destroyed in the flames. Eventually the fire in the town centre burnt itself out and some properties around the centre were demolished to prevent it spreading to the outskirts.

The town had contained about 300 houses, of which about 180 were destroyed, but fortunately no-one died. As Mary Jones reports in her 1875 ‘History of Chudleigh’ ‘The sympathy of the gentry of surrounding parishes was greatly excited, and clothing and food were poured into the town in abundance. […] The bell of the town-crier almost daily announced the arrival of these generous supplies, which were distributed in the Play Park. Boxes were fixed at each end of the town to receive the contributions of the many hundreds who came on the following Sunday from all parts.’ A relief committee was formed with the then Lord Clifford of the Ugbrooke Estate as chairman. Enough money was raised such that, together with the proceeds of insurance claims, all losses were reimbursed and by 1811 the town was rebuilt. The largest single amount of compensation was paid to a Mr Richard Rose, who used it to build the substantial new coaching hotel which became the Clifford Arms.

Fore Street, Chudleigh (September 2009). The featured building is The Old Coaching House hotel, which until 1971 was named the Clifford Arms. In the 19th century, until the railway arrived in the 1880s, coaches left here daily for (and arrived from) Exeter, Bath, Bristol, London and Plymouth. It was rebuilt in 1808 using compensation money after the great fire of 1807. Unfortunately this building was badly damaged by fire in December 2011, and at the time of writing is shrouded in scaffolding.

Fore Street, Chudleigh (September 2009). The featured building is The Old Coaching House hotel, which until 1971 was named the Clifford Arms. In the 19th century, until the railway arrived in the 1880s, coaches left here daily for (and arrived from) Exeter, Bath, Bristol, London and Plymouth. It was rebuilt in 1808 using compensation money after the great fire of 1807. Unfortunately this building was badly damaged by fire in December 2011, and at the time of writing is shrouded in scaffolding.

The photo below is from a 1904 postcard of roughly the same scene. Clearly at that time there was very little traffic, and what there was would not have been fast moving, but interestingly there is a car parked in front of the hotel. (The image isn’t large or distinct enough for clear identification, but it might be a De Dion-Bouton.)

(from the Chudleigh History Group website)

(from the Chudleigh History Group website)

In an attempt to prevent future fires, thatched roofs were not permitted on replacement buildings, and wherever possible the roads were widened to 32 feet and any obstructions removed. This had a significant effect on the appearance of the town centre area. Arguably many of the older properties would have been demolished anyway by now and the main thoroughfares widened, as they have in many other places, but because of the fire this happened earlier in Chudleigh than elsewhere.

Old Exeter Street (April 2013). The widening that occurred with the rebuilding can be seen here, as far as the white house on the left side of the road.

Old Exeter Street (April 2013). The widening that occurred with the rebuilding can be seen here, as far as the white house on the left side of the road.

Buildings in Clifford Street (previously Mill Street) were also destroyed as far south as the site now occupied by the former Wesleyan Chapel, but its narrow meandering medieval street plan was retained presumably because the plots the houses occupied did not have the depth to allow rebuilding further back, and also there was no pressure to improve access for coaches, as there was on the main road.

Sketches made soon after the fire show that many limestone walls and chimneys survived the blaze, and many were then retained as the core of the replacement buildings. Unusually large scale chimneys of a 17th century form can be seen on both sides of New Exeter Street, built into dwellings of fairly modest status.

The eastern side of New Exeter Street (April 2013)

The eastern side of New Exeter Street (April 2013)

…. and the other side

The replacement houses were built in the fashion of the day and doubtless introduced a more orderly appearance than the irregular, vernacular buildings that would have been there before. This does not seem to have damaged the attractiveness of the town to new residents, with several new villas and townhouses being built in the town soon afterwards.

The Bishop Lacy Pub, dating from the early 16th century, has a carved oak roof structure with wind braces over its formerly open hall. It is named after Edmund Lacy, who was Bishop of Exeter from 1420 to 1445. Prior to that he had been Dean of the Royal Chapel, and in that capacity accompanied King Henry V to the Battle of Agincourt in 1415.

The Bishop Lacy pub (April 2013)

The Bishop Lacy pub (April 2013)

Part of the front of Old House, Fore Street, Chudleigh (September 2009) The plaque reads ‘John Pinsent of Lincoln’s Inne, esquire, boren in this Pish hath erected this for a Free School and Endowed it with £30 per annum for ever 1668′. (As a grant intended mainly to pay wages and other running costs, £30 in 1668 would be worth at least £120,000 today.) John Pynsent was born in Chudleigh in 1807. He had embarked on a legal career in London and married into the Clifford family, who were established local gentry. In 1640 he was left a substantial legacy by his father-in-law Simon Clifford, who lived at Ware Barton. A few years later Pynsent acquired (possibly by purchase) an extraordinarily lucrative legal post in Westminster, which he was clever enough to hold onto throughout the Civil War, the Interregnum and the Restoration, until his death in 1668. His earnings enabled him to acquire substantial estates in Leicestershire, Oxfordshire and Surrey. (Biographical information on John Pynsent provided by Brian Pinsent, from his own research.)

Part of the front of Old House, Fore Street, Chudleigh (September 2009) The plaque reads ‘John Pinsent of Lincoln’s Inne, esquire, boren in this Pish hath erected this for a Free School and Endowed it with £30 per annum for ever 1668′. (As a grant intended mainly to pay wages and other running costs, £30 in 1668 would be worth at least £120,000 today.) John Pynsent was born in Chudleigh in 1807. He had embarked on a legal career in London and married into the Clifford family, who were established local gentry. In 1640 he was left a substantial legacy by his father-in-law Simon Clifford, who lived at Ware Barton. A few years later Pynsent acquired (possibly by purchase) an extraordinarily lucrative legal post in Westminster, which he was clever enough to hold onto throughout the Civil War, the Interregnum and the Restoration, until his death in 1668. His earnings enabled him to acquire substantial estates in Leicestershire, Oxfordshire and Surrey. (Biographical information on John Pynsent provided by Brian Pinsent, from his own research.)

He purchased an acre of land next to the church yard and intended to build a school for the free education of the children of Chudleigh. He died before it was completed. It was originally built to accommodate twenty boys. The school was successful and by the 1860s had grown in size and had a good reputation, but was expensive to run and in need of refurbishment. It was rescued in the 1870s when old boys contributed to building repairs, and only finally closed as a school in 1913. It was then a private house until 1964, when it became a guest house. It is now a B&B.

Chudleigh church, with Old House next door. The handsome tower is thought to date from the first half of the 14th century, although there was a church building here for many hundreds of years before that.

Chudleigh church, with Old House next door. The handsome tower is thought to date from the first half of the 14th century, although there was a church building here for many hundreds of years before that.

The Teign valley near Chudleigh. The cottages are on the B3193 just below Lyneham Wood. (October 2009)

The Teign valley near Chudleigh. The cottages are on the B3193 just below Lyneham Wood. (October 2009)

The next photo shows the river from the same field. Few tributary streams of any size join the river between Dunsford and Chudleigh, so the river does not grow appreciably in size in this section.

On the eastern side of the valley there are also three villages: Doddiscombsleigh, Ashton and Trusham.

Doddiscombsleigh is set just above the Shippen Brook, one of the small streams that flows down from the Haldon Hills to the Teign. It takes its name from the family that owned the manor at one time – a Sir Ralph Doddescomb was living in the manor house during the 13th century, although the settlement was still known as Legh-Peverel in church records of the 14th Century after the Legh family, who owned it before the Doddescombs. The Doddescomb name disappeared in the 14th century when the last male Doddescomb died, leaving five daughters, whereupon the manor was divided up by marriage. Town Barton, a large ex-farmhouse to the east of the village centre that now operates as a B&B, is thought to be on the site of the old manor house, which is mentioned in the Domesday Book (1086), at which time it was owned by Godbold the Bowman and the place was called Terra Godeboldi after him. It is probable that Godbold was given the land here because he was a bowman in King William’s all-conquering 1066 army, displacing the previous owner, recorded in Domesday as a Saxon called Alsi.

Town Barton, Doddiscombsleigh (March 2013)

Town Barton, Doddiscombsleigh (March 2013)

The present building dates from the early 17th century; it isn’t clear if it incorporates any remnants of the original, and it was given what Teignbridge Council’s Character Appraisal describes as ‘something of a fashionable facelift’ in about 1840. In 1775it was noted that Town Barton was renowned for its twenty acres of orchard which produced “remarkably fine cider”, most of which would presumably have been consumed in the local hosteleries.

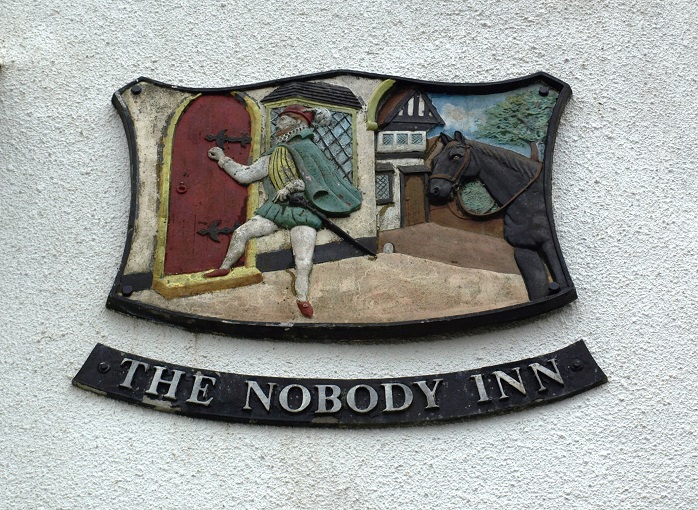

At the time this wouldn’t have included the Nobody Inn, which became a pub (originally the ‘New Inn’ in the mid-19th century, although the building dates from the 17th century. Apparently it takes is name from the unfortunate moment during a former landlord’s wake when his coffin was brought back to an empty pub.

The Nobody Inn, Doddiscombsleigh (March 2013)

The Nobody Inn, Doddiscombsleigh (March 2013)

The pub sign seems to depict something else – the man’s clothes appear to be from the 17th century and no coffin is in view, although perhaps the black horse is significant -? Or maybe it’s just a traveller finding nobody in.

Town Barton is right next to St Michael’s church. It is thought that the present building dates from the early 15th century, and that there was an earlier Anglo-Saxon church on the same site probably well before 1000 AD, parts of which have been incorporated into the later structure.

The interior features include a wood carving depicting The Last Supper framed within an imposing reredos, and floor memorials to various members of the Babb family, the biggest landowners hereabouts during the 16th and 17th centuries. There are also some excellent stained glass windows that have survived more or less intact for over 500 years, and are among the best in Devon. The Seven Sacrements window in particular is much admired, as it is said to contain the most complete in situ such composition in any English church.

The Seven Sacrements window, Doddiscombsleigh church (March 2013)

The Seven Sacrements window, Doddiscombsleigh church (March 2013)

There is a central seated figure of Christ with blood lines running from his hands, feet and heart to the seven small panels. The figure of Christ is of Victorian glass but much of the glass in the panels is medieval, although pieces have clearly been moved around during the restorations of 1762 and 1879 (and possible earlier restorations that have not been recorded). The top left hand panel represents the Holy Communion, below that is Marriage, and bottom left is Confirmation. The central bottom panel represents Confession or Penitence. The top right hand panel shows Ordination, and the middle one Baptism, and the bottom right panel the Last Rites.

St Michael’s church, Doddiscombsleigh (March 2013)

St Michael’s church, Doddiscombsleigh (March 2013)

The windows were restored in 1879 by a specialist firm of stained glass makers (Clayton & Bell) at their own expense, because they considered them so important. (However, experts are now very critical of this work: new figures were added, existing figures were given new heads, whole panels were re-arranged and even the heraldic devices moved around. Further, none of this was apparently done to match designs that still exist elsewhere by medieval craftsmen from the same workshop, and the thinking behind their decisions was not recorded.)

Another of the medieval stained glass windows – this one depicts St John the Evangelist, the Virgin Mary, and St Paul, with the Chudleigh family arms of three linked flags – the Chudleighs were lords of the manor at neighbouring Ashton when the church was built, and were linked by marriage to the Doddiscombs.

Another of the medieval stained glass windows – this one depicts St John the Evangelist, the Virgin Mary, and St Paul, with the Chudleigh family arms of three linked flags – the Chudleighs were lords of the manor at neighbouring Ashton when the church was built, and were linked by marriage to the Doddiscombs.

The area north of Doddiscombsleigh is the valley of the Sowton Brook, that joins the Teign near Bridfordmills. This is a view looking south west towards Doddiscombsleigh from the minor road that runs past the earthwork of Cotley Castle, with the woods of Wilhayes Brake in the middle distance. (September 2013)

The France Brook flows in a small valley between Doddiscombsleigh and the Haldon Hills, which forms the eastern boundary of the Teign catchment.

Looking up the valley of the France Brook, with the wooded Haldon Ridge on the horizon (March 2013)

Looking up the valley of the France Brook, with the wooded Haldon Ridge on the horizon (March 2013)

Dunchideock is a scattered settlement east of Doddiscombsleigh, in the foothills of Haldon. Although only three miles from the outskirts of Exeter, it feels as if it is buried deep in the countryside.

St Michael’s church was built of local red sandstone in the 14th century.

Steps up to Dunchideock church (September 2013)

Steps up to Dunchideock church (September 2013)

The intricately carved rood screen dates from the 15th century.

Interior of Dunchideock church, showing the rood screen, the rood cross above (to the right of the pillar) and the pine wood roof.

Interior of Dunchideock church, showing the rood screen, the rood cross above (to the right of the pillar) and the pine wood roof.

The rood cross above the screen was set up as a memorial to two brothers killed in the First World War, one of whom went down with the battle cruiser Indefatigable, which was sunk by enemy fire in the early stages of the Battle of Jutland in 1916. The ship exploded after its ammunition magazines caught fire; of the crew of 1019 men only two survived – they were picked up by a German torpedo boat.

The roof has several carved and painted bosses, including this one of a grotesque female head wearing a wimple, a garment worn by women at certain times during the medieval period to frame the face – it was considered unseemly for a married woman to show her hair.

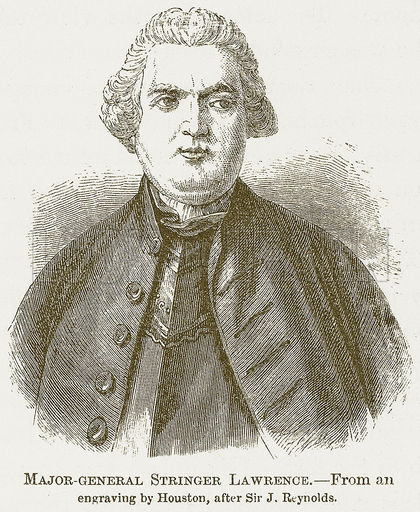

The church contains an elaborate monument to General Stringer Lawrence (1697-1775), known as ” the father of the Indian Army”, who commanded the East India Company’s troops for most of the twenty years from 1747, battling against the French for control of the south of India. He could certainly not be described as handsome; this portrait sketch is probably somewhat flattering, when compared both to the oil painting by Joshua Reynolds on which is supposedly based, and another portrait painted by Thomas Gainsborough.

The monument includes a typically effusive (and abstruse) epitaph, part of which reads:

Born to command, to conquer, and to Spare

As Mercy mild, yet terrible as War

Here LAWRENCE rests: the Trump of honest Fame

From Thames to Ganges has proclaimed his Name

In vain this frail Memorial Friendship rears

His Dearest Monuments an Army’s Tears

His Deeds on fairer columns stand engrav’d

In Provinces preserved and Cities fav’d

On his death Stringer Lawrence bequeathed his fortune to his friend Sir Robert Palk of Haldon House who, as noted above, erected Lawrence Castle (aka Haldon Belvedere) in his memory. Although today we might have a different perspective on imperialist military ventures, in his day we was much honoured. The East India Company erected a monument to his memory in Westminster Abbey, and a statue of him, dressed in classical Roman Army uniform, stands in the Foreign and Commonwealth Office.

Also in Dunchideock is this much photographed building called The Old Post Office which, as well as a post office, has been a schoolroom and a cobbler’s shop. It has 17th century origins, with additions in the 19th century and later.

The Old Post Office, Dunchideock (September 2013)

The Old Post Office, Dunchideock (September 2013)

Higher Ashton is situated in a quiet position on a hillside above the valley of the France Brook, about a mile from the Teign.

Higher Ashton (March 2013) The building on the right is Rainbow Cottages, which used to be almhouses in the 18th century, although they probably originated in the 16th or 17th century as a cross passage house i.e. where a passage runs through the building from the front to the back door.

Higher Ashton (March 2013) The building on the right is Rainbow Cottages, which used to be almhouses in the 18th century, although they probably originated in the 16th or 17th century as a cross passage house i.e. where a passage runs through the building from the front to the back door.

The early 15th century church has a dramatic setting high on a rock outcrop and dominates the village.

St John The Baptist church, Higher Ashton (April 2013)

St John The Baptist church, Higher Ashton (April 2013)

This is another country village church with an unusually fine set of rood screen paintings, considered by the author of the Listed Buildings entry to be ‘probably the best in the county’.

Part of the decorated rood screen

Part of the decorated rood screen

… and some of the figures on the other side of the screen.

Church historians consider these to be particularly unusual as the Latin inscriptions on the scrolls are not taken directly from the Bible, but from readings, antiphons and chants used in the mass and the daily office of the church. The figures are in 16th century dress and given their position in a private chapel that used to house the Chudleigh family vault, it’s also possible that they are likenesses of members of that family alive at the time.

Below the church is Place Barton, a large group of buildings dating from the 16th century, originally developed by the Chudleigh family as a mock-fortified courtyard mansion with formal gardens and a large deer park. The Chudleighs were lords of the manor here from 1320 to 1745. The current owners have restored the Great Barn and now offer it as a wedding venue.

Buildings at Place Barton (April 2013). The Great Barn is on the right.

Buildings at Place Barton (April 2013). The Great Barn is on the right.

The Shippen Brook flows south from Doddiscombsleigh to Higher Ashton, where it is channelled right next to the boundary wall of Place Barton, just before it meets the France Brook.

The Shippen Brook next to the wall of Place Barton (April 2013)

The Shippen Brook next to the wall of Place Barton (April 2013)

Another of the streams that rises on the Haldon Hills and flows west into the Teign is Bramble Brook, seen here at Bramble Bridge, a mile east of Trusham.  Bramble Bridge (April 2013)

Bramble Bridge (April 2013)

Trusham

Trusham is a small, compact village, which developed from a cluster of interlinked farmsteads. Thus its older houses are farmhouses, with their farm buildings clustered around them. The village remained an agricultural community until the 1930s, when new houses began to be built at the south-western end of the village. Since then, and especially during the 1970s and 80s, more new houses have been built where once there were orchards and fields.

The only pub, the Cridford Inn, claims to be the oldest in Devon and possibly the oldest in England, dating from AD825. It was supposedly a nunnery and then a farm, and the main building was remodelled in 1081.

However in June 2019 John Dyer a long term Trusham resident wrote to me to provide a different perspective. Commenting on the supposedly ancient stained glass window he said ‘I have a press cutting from the Mid Devon Advertiser of an interview with the first landlady a Mrs Gubbins who told them she had made this stained glass window herself. He goes on: ‘The whole Cridford Inn advert is a sham. The New Inn closed in the early 1920s. It was at the top of the village and replaced an earlier Inn which burnt down. There is no evidence of an Inn at Cridfords until Mrs Gubbins opened in the early 1980s.’ And Mr Dyer says it wasn’t a Devon Longhouse – it has no cross passage, and isn’t sunk into the hillside whereby the living accommodation is higher than the animal accommodation.

Mr Dyer also thinks that the date of 1081 is highly unlikely. ‘In the restaurant area to the left of the bar, through which you pass to go to the toilet, is a glass or perspex panel let into the floor boards through which you can see a section of the original flooring. The floor is made of small flat pebbles (cobbles) placed on edge. Pebbles such as you would find beside a river bank. We have a similar floor exposed in one of our fields nearby where stood a contemporary dwelling (Pristons) now overgrown with only the foundations remaining.’ It’s these pebbles that incorporate the date 1081. But he says look at it from the other side. Mr Dyer owns a cottage built in 1799, where his grandfather ran the local dairy, and he bought this cottage in 1914. ‘We recently uncovered a bread oven identical to the one in the Cridford Inn, which is about ten feet from the exposed floor. There may have been farm cottages here in medieval times but I favour 1801 as being relevant to the then, modernisation, of these cottages to the style we see today.’ He thunks that the rhetoric about Civil War ghosts and nuns as ghosts has been invented recently.

Dyer says ‘The Cridford buildings were a small farm milking a small herd of cows. The part of the building on the left, as viewed from the road, was the dwelling house. Towards the right (wherein the stained glass window has been inserted) was used as an out house. Sheep dogs were kennelled there. The windows were unglazed. This is now the bar area. The adjacent room up the steps from the bar was added much later. At the rear was a set of rustic steps which lead to a toilet.’

The window that is said to date from the 15th century. (March 2013)

The window that is said to date from the 15th century. (March 2013)

Just along the road from the Cridford Inn is a remarkable group of buildings: The Old Rectory is a late 15th century house (originally a farmhouse, later a rectory) with two adjacent 16th century cob and thatch outbuildings. All three have a cruck roof structure, and in the house this is blackened by soot and smoke, indicating that when the house was first built it would have had an open hearth in the hall. The opening in the roof through which the smoke was supposed to escape is also still there. (Cruck framing involves the use of large curved or bent timbers, linked by a tie beam, that lean inwards to form the framework of both walls and roof. Crucks were originally made by splitting the trunk and main branch of a suitably shaped tree, but such trees were also in demand for shipbuilding, and few cruck frames were used in buildings after the 16th century.) The Listed Building entry for The Old Rectory says that the house may be on or near the site of the Domesday Manor of Trisma, and that it has two oak windows that may date from around 1500 – clearly old windows are a speciality of Trusham. While it’s common for a well sited house to be maintained and modernised, and perhaps extended, in stages by a succession of owners over a long period of time, it is rare for small barns or storehouses like these to survive. Usually very old ones like this will be considered too small or not capable of being altered for modern uses., or will have deteriorated beyond repair long ago.

The Old Rectory, Trusham (April 2013). The two adjacent outbuildings are shown below.

The Old Rectory, Trusham (April 2013). The two adjacent outbuildings are shown below.

The late 15th century is clearly a very long time ago, but perhaps for a minute it’s worth pondering what life was like for the inhabitants of this house and their neighbours when it was first built. Most people who lived in small villages like Trusham would have worked on the land. They may have had some draught animals – possibly a mixture of horses and oxen – but otherwise everything would have had to be done by hand. Men spent their days in the fields, ploughing, weeding, sowing seed, fertilizing, or harvesting, depending on the season. Women also helped in the fields during harvest time, but mainly they devoted themselves to household tasks such as cooking, cleaning and sewing, and were also usually responsible for looking after the domestic livestock; families typically had at least one cow, and some smaller animals such as pigs, goats, chickens, and geese.

There was no piped supply of water, it all had to be carried to where it was needed, but this was not too arduous here due to the proximity of a small stream that still flows next to the road through the village, and possibly the house had its own well. The only sources of light would have been hearth fires, torches made from faggots of wood, crude lamps burning animal fat, and candles made from tallow or, if you could afford it, beeswax. So the village would have been very dark at night, and whether or not the moon was visible would determine what, if any, outdoor activities were feasible. In order to meet their own needs and fulfil their obligations to the lord of the manor, many people would have worked from daybreak to dusk in all weathers. The only days off were Sundays, when everyone was expected to attend church, and special occasions such as feast days and weddings. This sounds hard, and no doubt it was very tough at times, but people were generally physically stronger than we are now, and arguably an outdoor life is preferable to being shut up in a noisy, polluted factory all day, which is what happened later to village folk forced to migrate to cities and towns for work.

Life was far more precarious than now. The average life expectancy in Britain was only about 30 years, but this is slightly misleading due to the very high levels of infant mortality, so if you made it to adulthood, you would be unlucky not to make it at least into your 50s. But infectious diseases were a constant threat, and by 1500 the population had still not recovered to levels of 150 years previously, after the ‘Great Pestilence’ (now known as the ‘Black Death’) that had killed about 20% of the population. And there were further severe outbreaks of the plague in the 1470s, during which up to a third of the then population may have perished. However, infectious diseases were far more virulent in towns and cities, so possibly people in Trusham were not so much affected.

Printing had begun in England in the 1470s and it’s estimated that by 1500 there were more than twenty million printed books in Western Europe. But it’s likely that for several decades after 1470 the only books in the village would have been those used by the priest to conduct church services. Around 1500 the village inhabitants would have spoken a local dialect of what is now termed Middle English – a hundred years or so earlier Chaucer wrote The Canterbury Tales in a London dialect of Middle English, which a modern reader can’t properly follow without expert translation. So if we were somehow parachuted into Trusham in 1500 (in the Tardis, perhaps) I don’t think we’d understand much of what the locals were saying. But the advent of printing, and in particular the availability of standardised, printed English Bibles and Prayer Books, which were read to church congregations from the 1540s onward, meant that a generation or two later ordinary people started to become familiar with a standard language, and the era of Modern English was underway.

What would they have looked like? There are very few contemporary illustrations of medieval village life as ordinary people were not considered to be interesting subjects. However, some years later, in the 1560s, Pieter Brueghel (the Elder) made the life and manners of peasants the focus of a series of works that now provide important pictorial evidence about both physical and social aspects of life at that time. He was Flemish, but it’s reasonable to suppose that a similar occasion in England would have looked much the same. The painting reproduced above is ‘The Peasant Dance’ from 1567/8; the original is in the Kunsthistorisches Museum in Vienna.