This stretch of the Teign catchment can be divided into three distinct sections. Firstly, the open valley section of about two miles from Chagford Bridge to where the gorge begins, just downstream of Dogmarsh Bridge, overlooked by Castle Drogo. Secondly, the gorge itself, about three and a half miles long, with crossing points at Fingle Bridge and Clifford Bridge, and three hill forts on the summits above the gorge: Prestonbury, Cranbrook Castle and Wooston Castle. The gorge ends at Steps Bridge, from where the valley broadens out for a mile until the river makes a 90 degree turn to flow south east, just past the village of Dunsford.

Moretonhampstead is also included in this section of the website, as the town is only just over three miles south of the gorge, between the Teign and Bovey valleys.

Chagford Bridge in high summer (July 2009)

Chagford Bridge in high summer (July 2009)

Chagford Bridge (July 2009), situated just below the town, once on the main route north from Chagford, is now on a minor road to Gidleigh and Sandy Park. Chagford means ‘gorse ford’ from the old local dialect word chag (broom, gorse), the ford being that over the Teign which is now crossed by this bridge. Documents show that a bridge existed here before 1224, that a bridge on this site, possibly this one, was repaired by the parish between 1560-92. In his well known 1954 history of Devon, W.G. Hoskins thinks that this may have been the bridge seen by Leland. This is a reference to John Leland who, in the 1530s, authorised by King Henry VIII, spent several years travelling round religious houses, compiling numerous lists of significant or unusual books in their libraries, in many cases shortly before they were dissolved, and later undertook extensive travels to study and record English and Welsh topography and antiquities – he was in the West Country in 1542, which is presumably when he saw Chagford Bridge.

Chagford Bridge (July 2009), situated just below the town, once on the main route north from Chagford, is now on a minor road to Gidleigh and Sandy Park. Chagford means ‘gorse ford’ from the old local dialect word chag (broom, gorse), the ford being that over the Teign which is now crossed by this bridge. Documents show that a bridge existed here before 1224, that a bridge on this site, possibly this one, was repaired by the parish between 1560-92. In his well known 1954 history of Devon, W.G. Hoskins thinks that this may have been the bridge seen by Leland. This is a reference to John Leland who, in the 1530s, authorised by King Henry VIII, spent several years travelling round religious houses, compiling numerous lists of significant or unusual books in their libraries, in many cases shortly before they were dissolved, and later undertook extensive travels to study and record English and Welsh topography and antiquities – he was in the West Country in 1542, which is presumably when he saw Chagford Bridge.

The river between Chagford and Rushford Bridges (July 2009)

The river between Chagford and Rushford Bridges (July 2009)

Brown trout are found in the stretch of the river between Chagford Weir and Rushford Bridge. Below Rushford Bridge fishermen look for sea trout and, in the right conditions, salmon.

Rushford Bridge (July 2009) In its entry in British Listed Buildings, this is described as ‘probably 17th century, but may be earlier’. It was widened in either the late 18th century or the early 19th century, and refurbished in 1911, when the cast iron strainer bars were probably installed to hold it together.

Rushford Bridge (July 2009) In its entry in British Listed Buildings, this is described as ‘probably 17th century, but may be earlier’. It was widened in either the late 18th century or the early 19th century, and refurbished in 1911, when the cast iron strainer bars were probably installed to hold it together.

The river from Rushford Bridge (July 2009). The strange water creature is a black dog.

The river from Rushford Bridge (July 2009). The strange water creature is a black dog.

Rushford Mill was the original manorial corn mill, and it is likely that the stepping stones which spanned the river Teign were at one time the main crossing point from the manor to Chagford. It was normal for each manor to have its own grinding mill and then everybody who was affiliated to that manor were compelled to bring their corn for grinding, be it for flour or grist (cattle feed). Very few grain crops are now grown in the area, but until World War II rye and oats were grown quite extensively on the lower edges of Dartmoor, hence the need for a local mill, and it is thought that Rushford Mill was worked until 1947.

A postcard of Rushford Mill, possibly taken around 1910 (from the www.sharehistory.org website).

A postcard of Rushford Mill, possibly taken around 1910 (from the www.sharehistory.org website).

The A382 over Dogmarsh Bridge (February 2011). This bridge was built around 1840. There was a bridge over the Teign near here mentioned in documents from the 17th century, but it is thought to have been a short distance upstream.

The A382 over Dogmarsh Bridge (February 2011). This bridge was built around 1840. There was a bridge over the Teign near here mentioned in documents from the 17th century, but it is thought to have been a short distance upstream.

Looking upstream from Dogmarsh Bridge (February 2011)

Looking upstream from Dogmarsh Bridge (February 2011)

A distant view of Castle Drogo (on the horizon) and the woods at the western end of the Teign Gorge, from near Dogmarsh Bridge. (August 2011)

A distant view of Castle Drogo (on the horizon) and the woods at the western end of the Teign Gorge, from near Dogmarsh Bridge. (August 2011)

Five manors were included within the ancient parish of Drewsteignton, with the principal one being named Tainton. After the Norman Conquest the land was considered part of the estate of Okehampton, was awarded to a trusted friend of King William, and later passed by marriage to the Courtenays and then to the Carew family, who owned it until the end of the eighteenth century. Some time during the twelfth century a man named Drogo (aka Drew), was the sub-tenant of Tainton and the name became fixed as ‘Drogo’s Tainton’ otherwise ‘Teignton Drue’, meaning ‘Drew’s farm by the Teign’.

The main square in Drewsteignton (February 2011). The church dates mostly from the 15th century, and the ‘Drewe Arms’ pub from the 17th century. The pub was previously called ‘The Druids’ Arms’ but the name was changed in the 1920s when Julius Drewe became a big local landowner and built Castle Drogo nearby.

The main square in Drewsteignton (February 2011). The church dates mostly from the 15th century, and the ‘Drewe Arms’ pub from the 17th century. The pub was previously called ‘The Druids’ Arms’ but the name was changed in the 1920s when Julius Drewe became a big local landowner and built Castle Drogo nearby.

Castle Drogo was constructed from locally quarried granite between 1911 and 1930 and is considered to be the last castle built in England. It was commissioned by Julius Drewe, the founder of Home and Colonial Stores, a grocery stores business which until the 1960s was a presence on most high streets and at one time had 3,000 shops. Julius sometimes stayed with his cousin, who was the rector of Drewsteignton. This was probably what triggered his interest in building a house on the territory of his supposed ancestor, Drogo. In 1910 he bought 450 acres of land south and west of the village, including the site overlooking the Teign gorge on which he decided to build his castle.

Looking along the Teign gorge from the grounds of Castle Drogo (July 2012) The river can just be seen at the bottom of the valley.

Looking along the Teign gorge from the grounds of Castle Drogo (July 2012) The river can just be seen at the bottom of the valley.

Drewe employed Edwin Lutyens, probably the foremost country house architect of his time. Construction was interrupted by the First World War and by Drewe’s loss of interest in the project for a while due to the death of his son in the war. Interestingly, the lengthy period of construction of Castle Drogo coincides with that of Lutyens’ biggest project: that of the central showpiece area of New Delhi as a new capital city of India. Julius Drewe’s descendants gave Castle Drogo to the National Trust in 1974.

The view from the terrace at Castle Drogo (July 2012)

The view from the terrace at Castle Drogo (July 2012)

In order for the building to have a castellated outline it has flat roofs, and the pipework is hidden within the walls. These design features have caused continual leakage and water penetration problems. For the last few years the National Trust has run a campaign for funds to replace the roof, re-point the walls, rebuild the parapet and refurbish all the windows. Apparently, the problems have been exacerbated by the heavier downpours being experienced now as a result of climate change.

Part of the western elevation of Castle Drogo (July 2012). Note how each granite block has been precisely carved to form angled corners, lintels, window frames, etc.

Part of the western elevation of Castle Drogo (July 2012). Note how each granite block has been precisely carved to form angled corners, lintels, window frames, etc.

Interior of Castle Drogo (August 2011). The interior walls are mostly plain granite.

Interior of Castle Drogo (August 2011). The interior walls are mostly plain granite.

A bed of pick-your-own produce in the Castle Drogo garden (August 2011). Lutyens designed the layout of the gardens, with some advice from Gertrude Jekyll, with whom Lutyens had collaborated since the late 1880s. The original planting scheme was by another garden designer, George Dillistone.

A bed of pick-your-own produce in the Castle Drogo garden (August 2011). Lutyens designed the layout of the gardens, with some advice from Gertrude Jekyll, with whom Lutyens had collaborated since the late 1880s. The original planting scheme was by another garden designer, George Dillistone.

The rose garden, Castle Drogo (July 2012).

The rose garden, Castle Drogo (July 2012).

Part of the front elevation of Caste Drogo (August 2008). The inscription over the door is ‘Drogo Nomen Et Virtus Arma Dedit’, which means ‘Drogo is my name and valour gave me arms’.

Part of the front elevation of Caste Drogo (August 2008). The inscription over the door is ‘Drogo Nomen Et Virtus Arma Dedit’, which means ‘Drogo is my name and valour gave me arms’.

The picturesque Fingle Bridge is situated on an ancient track from Drewsteignton to Moretonhampstead. It is thought to date from the early 17th century, and consists of three arches set on massive piers, the cutwaters of which support recesses designed to let pedestrians move aside to allow a loaded packhorse to pass

Fingle Bridge, with the imposing hillside topped by Prestonbury Castle hillfort in the background (July 2012).

Fingle Bridge, with the imposing hillside topped by Prestonbury Castle hillfort in the background (July 2012).

Packhorses were able to carry up to 400lb (180kg) each and travelled in trains of up to 40 animals. They could travel around 15 miles a day in hilly country, perhaps up to 25 miles on the flat. The group could get strung out over a long distance; they followed a lead horse, who knew the route and sometimes had bells attached to encourage the followers to keep up. Goods were carried in panniers slung on either side of the horse from wooden pack frames. The distance between the parapets of Fingle Bridge is only seven feet, and to allow clearance for the panniers the parapets are very low, as can be seen here, they only just come above an adult’s knees.

The roadway over Fingle Bridge (July 2012).

The roadway over Fingle Bridge (July 2012).

Fingle Bridge was built to enable the transport of the products of local industries, particularly timber, bark and charcoal, and corn ground in a nearby watermill (which was destroyed by fire in 1894).

The approach to Fingle bridge (February 2011). This shows how the bridge narrows sharply in the middle. It has never been widened because no vehicles traffic is expected – there is no road up the steep south side of the gorge.

The approach to Fingle bridge (February 2011). This shows how the bridge narrows sharply in the middle. It has never been widened because no vehicles traffic is expected – there is no road up the steep south side of the gorge.

Fingle Brook, just north of Fingle Bridge (February 2011)

Fingle Brook, just north of Fingle Bridge (February 2011)

The bridge takes its name from this stream that rises near Whiddon Down and joins the Teign close to the bridge. In Victorian times the gorge was known as the Fingle Valley.

The Fingle Bridge Inn viewed from the bridge (February 2011)

The Fingle Bridge Inn viewed from the bridge (February 2011)

This photo shows one of the recesses which enabled pedestrians to make way for horse traffic. The pub is popular with walkers.

Directly above Fingle Bridge is a steep hill crowned by the Prestonbury Castle hillfort. On the opposite side of the gorge is another, Cranbrook Castle, and a third, Wooston Castle, is in a strategic position further down the gorge on the south side. (There was never a castle building at any of these sites – these are honorary titles.) In each case there are a few remains of the original earthworks. Charles Merivale, a noted historian of the Roman Empire, speculated that these hill forts may have witnessed the final struggles between the Romans and the local British Celtic tribe, the Dumnonii. Having successfully gained control of South East England after the invasion in 43 AD, the Roman campaign to subdue the Western tribes was led by Vespasian, during which it is recorded that his forces captured twenty settlements including hill forts. During the hostilities Vespasian was reportedly badly injured, but he recovered and went on to become Roman Emperor for ten years from 69 to 79AD.

The river flowing through the gorge just downstream from Wooston Castle (July 2012).

The river flowing through the gorge just downstream from Wooston Castle (July 2012).

Clifford Bridge (July 2012). Built in the 17th century, originally only half this width, it was widened in the 19th century. It carries a minor road that goes over Mardon Down to Moretonhampstead.

Clifford Bridge (July 2012). Built in the 17th century, originally only half this width, it was widened in the 19th century. It carries a minor road that goes over Mardon Down to Moretonhampstead.

This road climbs steeply out of the gorge through dense woodland ….

and then emerges to provide views north west to the tops of the trees in the gorge around Wooston Castle (both July 2012)

In August 2013 it was announced that the Woodland Trust and the National Trust had jointly purchased a total of 825 acres of woodland in the gorge. The press release used the term ‘Fingle Woods’ – in fact the acquisition covered Wooston Castle Wood, Halls Cleave Wood and Cod Wood, together with the small outlying Butterdon Wood.

A aerial view of the Teign gorge woodlands from the Fingle Woods sales brochure © John Clegg & Co

A aerial view of the Teign gorge woodlands from the Fingle Woods sales brochure © John Clegg & Co

This is really good news – the gorge is a wonderful landscape feature, but these woods have been closed to the public until now, and the conifer plantation areas are unattractive. The plan is to create a network of new public footpaths, and gradually to clear out the 525 acres of commercial conifer plantings to allow native broadleaf species to recolonise the land over the coming decades. Existing fragments of ancient woodland will be retained. (Broadleaf species, mainly oak and beech, currently occupy about 20% of the land area.)

At the eastern end of the gorge Steps Bridge carries the B3212 over the river. It was built in 1816; in the 1950s its heritage listing described it as a 19th century restoration of a 16th century structure.

Approaching Steps Bridge from the west. (October 2009)

Approaching Steps Bridge from the west. (October 2009)

The river just upstream from Steps Bridge (October 2009)

The river just upstream from Steps Bridge (October 2009)

Moretonhampstead is an ancient market town with a population of about 4000 people It is situated at the edge of Dartmoor between the valleys of the Bovey and the Teign, on high ground above the Wray Brook, which joins the Bovey south of Lustleigh.

A wrought iron house sign by the church in Moretonhampstead (July 2012)

A wrought iron house sign by the church in Moretonhampstead (July 2012)

The Cross Tree (also known as the Dancing Tree) is one of the old landmarks of Moretonhampstead, and features in the 1882 novel ‘Christowell’ by R.D.Blackmore, the author of ‘Lorna Doone’. It was originally an ancient elm that grew by chance next to the Old Market Cross, a remnant of the original that was the preaching point around which Moretonhampstead was first established. The roots ousted the cross, which fell, breaking the shaft but leaving the head, in the centre of which is a Greek Tau Cross. The tree grew to be very large, and when an inn was opened close by in 1799 it was cut into the shape of a punch bowl, and a platform erected around it. There was enough room for thirty people to sit around the tree and six couples to dance, plus a band. During the Napoleonic Wars French prisoners-of-war on parole from Dartmoor Prison often assembled at the tree with their band. Some French prisoners were exchanged with their English counterparts and could return home. One such prisoner, who played the fiddle in the orchestra, sadly died the day before his exchange papers came through and is buried in the churchyard; his gravestone can be seen in the church doorway. The original tree blew down in 1903, after which it was replaced by a copper beech which was cut into a similar shape to the original, but evidently that has gone too as there is now a new young tree there – it must be difficult for mature trees to survive in the small stone pot surrounded by tarmac.

The Cross Tree as it now is (July 2012)

The Cross Tree as it now is (July 2012)

Cross Street, Moretonhampstead (July 2012)

Cross Street, Moretonhampstead (July 2012)

The building on the left is Mearsdon Manor. Recently the owner, Ian Mortimer, a writer and historian, applied to make alterations to this building. He has established that the latest date of construction for the property in its current form is 1525, but a detailed architectural survey has revealed that the front wall probably incorporates portions of an earlier medieval building. This confirms it as one of the earliest known townhouses in Devon, and perhaps the oldest for which there is a history of continuous ownership. The Listed Building entry notes that ‘It is said that this is the site of the Saxon Barton of circa 700 AD. Sir Philip Courtenay came into the possession of Moreton in 1309, when he enlarged and improved the Barton to become his manor house.’

Cyclists resting at the junction of Court Street and Pound Street, Moretonhampstead (July 2012). The sculpture on the wall is of a sparrowhawk by Roger Dean. The bird has become a town symbol, since when King John granted the town its charter in the thirteenth century, the rent was set at one sparrowhawk per year. It is not known whether this rent was ever paid.

Cyclists resting at the junction of Court Street and Pound Street, Moretonhampstead (July 2012). The sculpture on the wall is of a sparrowhawk by Roger Dean. The bird has become a town symbol, since when King John granted the town its charter in the thirteenth century, the rent was set at one sparrowhawk per year. It is not known whether this rent was ever paid.

Dunsford is an attractive village of about 700 people, with a strong community atmosphere.

Cottages in Dunsford , with the church tower behind (April 2015)

The Royal Oak pub and the church, Dunsford (October 2009). The church was built around 1430, the pub was presumably originally a private house, and looks like it was built around 1900. The landlords keep dogs, donkeys, ducks, miniature ponies, goats, cats, guinea pigs, giant rabbits & chickens for their own amusement and that of their customers.

The Post Office and stores, Dunsford (October 2009) At the time the board on the left was informing residents of the start of rehearsals for the annual pantomime by the village players. The building dates from the 16th century and was originally part of a farmhouse, probably the hall, heated by a fire in the exposed granite chimney stack. The Post Office is joined to the much larger Old Post Cottage, which is thought to be the service range of the farmhouse, built in the 17th century. It features a massive stepped gable chimney of finely-dressed granite blocks.

The Post Office and stores, Dunsford (October 2009) At the time the board on the left was informing residents of the start of rehearsals for the annual pantomime by the village players. The building dates from the 16th century and was originally part of a farmhouse, probably the hall, heated by a fire in the exposed granite chimney stack. The Post Office is joined to the much larger Old Post Cottage, which is thought to be the service range of the farmhouse, built in the 17th century. It features a massive stepped gable chimney of finely-dressed granite blocks.

Old Cawte Farmhouse is another fine 16th century building with a prominent chimney stack.

In the 12th century the manor of Dunsford was owned by the Fulfords and the family still live in Great Fulford, a Tudor mansion about 2 miles north west of the village. There are several monuments to Fulfords inside the church, the most impressive of which is this one to Sir Thomas Fulford (1553-1610) and his wife Ursula, who was the daughter of Richard Bampfield of Poltimore House.

The Fulford monument (April 2015).

The Fulford monument (April 2015).

The figures of the recumbent couple and their seven children, shown kneeling in line before an open Bible, are remarkably well preserved and still have some of their original colour.

The Fulfords also owned Lewishill, a substantial high quality house dating back to the late 15th century. It is situated close to the church, but set back from the road and can only be glimpsed from the churchyard through its surrounding trees.

A glimpse of Lewishill from Dunsford churchyard. (April 2015)

Doone Cottage, an attractive 17th century house of rendered cob construction, is located a little way out of the old village centre. It has a three room cross-passage layout typical of its period.

Crockernwell, close to the extreme northern edge of the Teign catchment, is a long established place, being mentioned in the Domesday Book, but has apparently never been more than a minor settlement.

The road through Crockernwell (April 2015). The building apparently jutting into the road on the right is the Old Post Office.

It has now been by-passed but until the new A30 was built it was on the main route from London to Cornwall. When the volume of traffic increased as roads were improved during the first half of the 19th century there was a demand for coaching facilities. Two substantial coaching inns, the Royal Hotel and the Golden Lion, were built in Crockernwell, and by the middle of the 19th century it also had a post office, coopers, blacksmiths, saddlers, butchers, masons, carpenters, wheelwrights and shoemakers, providing services both to travellers and the local rural population.

Court House, which was formerly the Royal Hotel (April 2015).

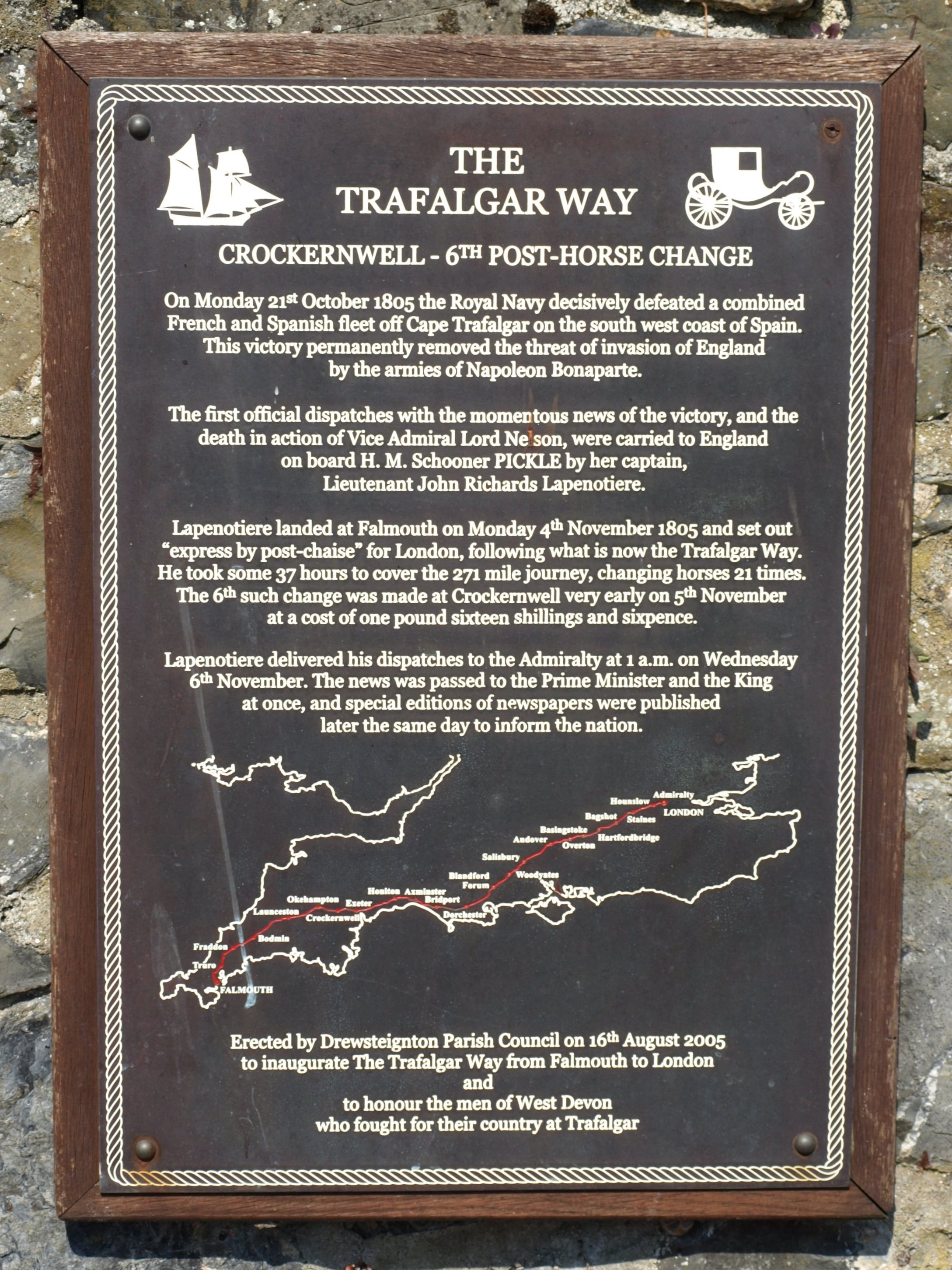

Crockernwell was one of the places that provided fresh horses to Lieutenant John Richards Lapenotiere when he carried news of the British victory at the Battle of Trafalgar from Falmouth to London on 5th November 1805. This is commemorated on a plaque just across the road from Court House.

Trafalgar Way plaque at Crockernwell (April 2015)

Lapenotiere travelled in a post-chaise, a four-wheeled closed carriage containing one seat for two or three passengers. They were built for long-distance travel, with horses being changed at intervals. In the 19th century post-chaises could be hired with the driver and two horses for about a shilling a mile.

A post-chaise on show at a carriage driving event.

Because the driver rode one of the horses, there were no reins and it was possible to have windows in front as well as at the sides. Being able to see out in the direction of travel would have made it a bit more pleasant for the passengers, but travelling non-stop at speed for 37 hours, the time it took Lapenotiere to reach London, must have been gruelling.