This page describes the area south of Newton Abbot drained by rivers and streams that flow into the Teign. In the eastern part this is mainly the Aller Brook and its small tributaries; the western part is drained by tributary streams of the Lemon south of the main river. The south eastern boundary of this part of the catchment skirts the built- up area of Torquay; the south western boundary runs between Ipplepen and Abbotskerswell to Denbury and then includes the area south of Bickington drained by the Kester Brook.

Considering the Aller catchment is quite a small area squeezed between Newton Abbot and Torquay, away from the larger villages and main roads it is surprisingly rural and quiet.

This is the scene close to Coffinswell church – the narrow lane on the left eventually leads to Kingskerswell (June 2014).

This is the scene close to Coffinswell church – the narrow lane on the left eventually leads to Kingskerswell (June 2014).

Originally the Aller Brook flowed in a shallow, wide valley from somewhere around Daccombe west to Kingskerwell and then north past Forde House to meet the Teign at Hackney Marshes. But nowadays it is difficult to see the river in anything like its natural state. Even here, south of Coffinswell and close to its source, it is almost hidden by vegetation.

Its course has been much altered and its flow contained within artificial channels and culverts, and more of this has taken place recently along the route of the new Kingskerswell By-Pass.

Here the river is flowing in a flood overflow channel close to Dacca Bridge, pending more work to restore the natural flow under the bridge. (June 2014)

Then in its final stretch just before it meets the Teign the Aller Brook flows in a straightened channel past the Brunel Industrial Estate, which is hidden behind the trees on the left. (September 2009)

Kingskerswell is the largest settlement in this area, with a population of about 5,000.  The junction of Fore Street and Dacca Bridge Road (June 2014). (The house on the right appears to be totally derelict, with creepers growing over the windows.)

The junction of Fore Street and Dacca Bridge Road (June 2014). (The house on the right appears to be totally derelict, with creepers growing over the windows.)

Kingskerswell is built along the Aller Brook valley and is still just separated from Newton Abbot to the north and the northern outskirts of Torquay to the south. It was originally established around the best crossing point of the Aller valley, where two spurs of land come close together. An ancient track from St Marychurch to Totnes used this crossing point, originally via a ford and later a bridge (Dacca Bridge).

Dacca Bridge today. (June 2014) The Heritage Listing says: ‘probably some medieval fabric, considerably rebuilt in 1693 and likely to have been repaired in the 19th century.

Dacca Bridge today. (June 2014) The Heritage Listing says: ‘probably some medieval fabric, considerably rebuilt in 1693 and likely to have been repaired in the 19th century.

This imposing 19th century warehouse constructed from limestone and sandstone, occupies a prominent position on the road leading down to Dacca Bridge, suggesting that this was once a major commercial thoroughfare.  Disused warehouse in Daccabridge Road (June 2014).

Disused warehouse in Daccabridge Road (June 2014).

The village originally grew up on the western bank of the river, where some old buildings still survive.

Tudor Cottage, Church End Road (June 2014). Tudor Cottage probably has 16th century origins and was once the Church House.

Tudor Cottage, Church End Road (June 2014). Tudor Cottage probably has 16th century origins and was once the Church House.

Pitt House (June 2014). Pitt House dates from the early 16th century and was originally a farm house that probably consisted of just three rooms open to the roof with a central hearth and a through passage from front to back. In the 1980s it was a restaurant. When this photo was taken it had just been re-thatched.

Pitt House (June 2014). Pitt House dates from the early 16th century and was originally a farm house that probably consisted of just three rooms open to the roof with a central hearth and a through passage from front to back. In the 1980s it was a restaurant. When this photo was taken it had just been re-thatched.

The ‘King’ in Kingskerswell reflects its early ownership by English royalty – by Edward the Confessor prior to the Norman Conquest and then by William and his descendants, until it was gifted by King Henry III to Sir Nicholas de Moels (or ‘Molis’) in 1230. Sir Nicholas made his career in the King’s service, holding many posts, including Sheriff of Devon, King’s Messenger to France, and military commander and Governor of Gascony in SW France (which had been in the possession of the English since 1152 when the future Henry II acquired it through his marriage to Eleanor of Aquitaine.)

Later, John Dinham (or ‘Dynham’) inherited the manor in 1381, and his family retained it until 1501. This effigy in the church of a man in armour is thought to be of him.

Effigy in Kingskerswell church (December 2013)

Effigy in Kingskerswell church (December 2013)

The remains of a manor house and associated farm buildings are situated close to the church, and are the subject of an ongoing archaeological and preservation project. The manor house is thought to have been built sometime between 1230 and 1295 by the de Molis family. Their involvement in national and international affairs would have given them high status and required a house to reflect their social standing and wealth. Unusually, it appears that it was largely abandoned as a family seat early as the 15th century possibly because the Dinhams of that time preferred to live at one of the other manors they owned, in East Devon. But some form of occupation continued, at least until the 17th century, when the ‘farm house’ building was constructed on the south end of the earlier house, but this suggests that it was lived in by a tenant farmer rather than the Lord of the Manor.

Remains of the manor house next to Kingskerswell church (December 2013).

Remains of the manor house next to Kingskerswell church (December 2013).

Modern-day visitors to the village cannot ignore the vast works involved in the construction of the Kingskerswell By-Pass, which blighted the area since work began in October 2012; it opened in December 2015. Given the rather grand title of the South Devon Link Road by its sponsors, it runs for 5.5km and connects the existing dual carriageway sections of the A380 between Newton Abbot and Torbay. It was budgetted to cost £110m, which works out at £20,000 per metre!  The Kingskerwell By-pass under construction, viewed from Priory Road (December 2013).

The Kingskerwell By-pass under construction, viewed from Priory Road (December 2013).

Kerswell Down, just to the west of the village, is the site of a late Bronze Age/early Iron Age field system, and in the 19th century a hoard of over 2,000 Roman coins was found here, near the church. Then in 1992, during early survey work for the By-Pass, evidence of a Roman settlement was found at Aller Cross, just north of the village, which was particularly interesting considering the paucity of evidence for Roman settlement south of Exeter. This site was excavated more thoroughly in 2012 when construction finally got under way, and this yielded a large number of Roman artefacts. The archeologists discovered a large rectangular ditched enclosure, which appears to have been modified three times, perhaps as a result of increasing wealth and the construction of more elaborate buildings inside the enclosure, the remains of which have unfortunately been destroyed by subsequent quarrying. The excavation also discovered a previously unknown medieval settlement dating from around the 13th century at Edginswell Lane, closer to the village. The medieval remains include the substantial foundations of stone walls, as well as a trackway leading to the building from the main road. It is possible that these buildings were abandoned when the Black Death arrived in Britain.

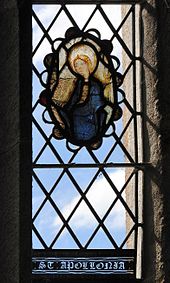

The church, which is dedicated to St Mary, may have parts dating to the 14th century, most notably the tower. The present building was started in the 1530s. As well as three effigies of the Dinham family, it has an uncommon image of Saint Apollonia, the patron saint of toothache sufferers, in the form of ancient stained glass in one of the south windows.

The building of the Newton Abbot to Kingswear railway line had a dramatic effect on Kingskerswell in the late 1840s as it was driven right through the centre of the village, causing the demolition of several properties, severance of the ancient crossing at Dacca Bridge, and disturbance to the natural drainage pattern of the local springs and streams.

The road over Rosehill Viaduct (June 2014).

The road over Rosehill Viaduct (June 2014).

The Rosehill Viaduct and the nearby Dobbin Arch were built in 1846-8 to span the railway and the re-routed river, which has been channeled to run right alongside the tracks.

The Aller Brook can just be seen next to the railway at Rosehill Viaduct (June 2014)

The Aller Brook can just be seen next to the railway at Rosehill Viaduct (June 2014)

Dobbin Arch, over the railway and river (July 2014)

Dobbin Arch, over the railway and river (July 2014)

There was a village station on this line between 1853 and 1964, which prompted wealthy businessmen from Torquay and Newton Abbot to build many large villas here, making it an early example of a commuter town.  This road junction, at the western end of Rosehill Viaduct, gives an impression of what the village was like before the major extensions of the 20th century. (June 2014)

This road junction, at the western end of Rosehill Viaduct, gives an impression of what the village was like before the major extensions of the 20th century. (June 2014)

In the 19th century Kingskerswell was well known for the production of cider and much of the land to the east of the main road now occupied by housing estates was then covered by apple orchards.

Abbotskersell is a pleasant village of about 1,500 people situated in a sheltered, fertile valley west of Kingskerswell.

An overview of the village from Priory Road (December 2013).

An overview of the village from Priory Road (December 2013).

The ‘kerswell’ in both Kings- and Abbotskerswell means ‘cress spring’, in the case of the latter the spring concerned probably feeds a small stream that flows east into the Aller Brook. In Saxon times the land was owned by King Edwy. He divided his local estates into two, keeping half for himself (hence Kings-) and giving the half to his granddaughter, Ethelhilda, who in turn gave it to the Abbey of Horton in Dorset as an endowment. Like its bigger neighbour, Abbotskerswell used to be known for its apple orchards and cider making. Henley’s Devonshire Cider was made from apples grown in orchards around the village, but little remains today.

Buildings around Abbotskerswell church (December 2013).

Buildings around Abbotskerswell church (December 2013).

St Mary’s church is of 13th century origin, but it was much altered in the 15th century when the 60ft high tower was added.  Abbotskerwell church (December 2013).

Abbotskerwell church (December 2013).

Then, like many village churches, it was rescued from dilapidation in the late 19th century, which among other things involved the rebuilding of some walls. During this process a large statue of the Virgin Mary was uncovered built into the splay of a 15th century window. The statue, which is hollowed out so that it is no more than 4ins thick, was seriously damaged before the builders realised it was there. Historians have speculated that it was plastered over (and subsequently forgotten about) around 1548, when emissaries of the (Protestant) Duke of Somerset were touring the country continuing the destruction of Catholic religious imagery started with the Dissolution of the monasteries in the reign of Henry VIII. Edward Seymour, Duke of Somerset, was Lord Protector of England during the minority of his nephew King Edward VI, the son of Henry VIII, in the period between the death of Edward’s father in 1547 and his own indictment in 1549 following widespread unrest caused by the ineptitude of his rule. A series of armed revolts broke out, fuelled by various religious and agrarian grievances, including the imposition of church services in English; one of the most serious rebellions was in Devon and Cornwall.

The remains of the Virgin statue in Abbotskerswell church (December 2013).

The remains of the Virgin statue in Abbotskerswell church (December 2013).

Houses still exist in the village which were originally built in the 1500s as farmhouses, including Court Farm, right next to the church and originally owned by the Abbot of Horton. However, the house was rebuilt in 1721 by the then owner, a Quaker farmer called James Tuckett. In 1839 there were still ten farms in the village, of which this was the largest.

Court Farm, next to the church (December 2013).

Court Farm, next to the church (December 2013).

Town Farm is another survivor from the 16th century.  Town Farm, Abbotskerswell (December 2013).

Town Farm, Abbotskerswell (December 2013).

Abbotskerswell Priory, situated on high ground on the outskirts of the village, was the home of a community of Augustinian nuns until 1983. In 1797 the nuns were living in a French community in Belgium, but were driven back to England by the effects of the French Revolution. They settled at what was originally Abbotsleigh House in 1861. The nuns lived as a closed order and had very little communication with the outside world until the 1950s. The Priory has now been converted into apartments for elderly people.

Abbotskerswell Priory (December 2013).

Abbotskerswell Priory (December 2013).

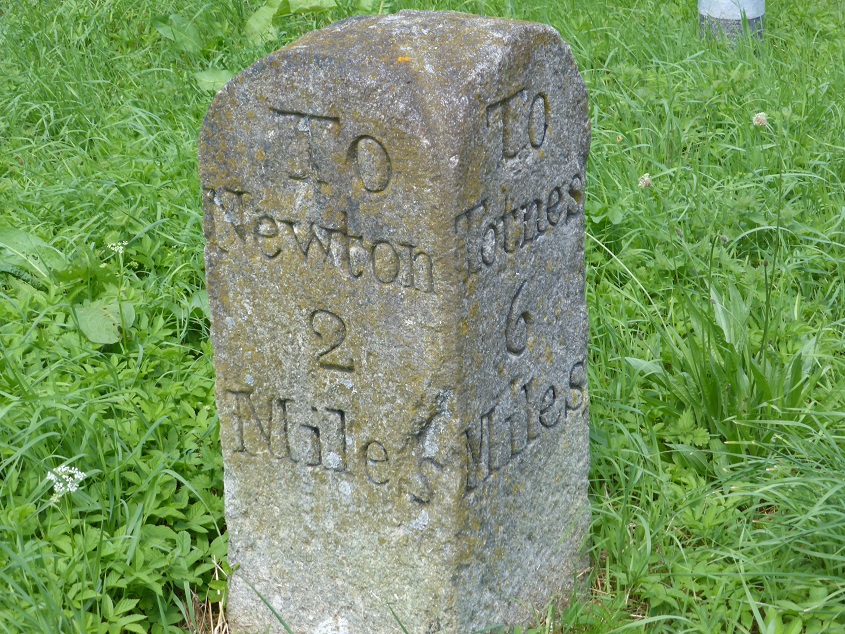

Two Mile Oak public house was built in the 16th century on an important junction south west of Abbotskerswell where the roads from Newton Abbot to Totnes and Denbury to Kingskerswell cross.

Two Mile Oak public house and crossroads (June 2014).

Two Mile Oak public house and crossroads (June 2014).

The old milestone at Two Mile Oak, indicating the origin of its name,

The old milestone at Two Mile Oak, indicating the origin of its name,

Coffinswell , a small picturesque village east of Kingskerswell, has several traditional Devon cob and thatch cottages, including this one that might well have featured on many calendars and biscuit tins!

Rose Cottage, Coffinswell (June 2014).

Rose Cottage, Coffinswell (June 2014).

The name of the village is apparently nothing to do with coffins or even wells per se, being derived from an ancient name for the area: Willa or Wille, where a stream-fed stream arose, and the Coffyn family, who were once lords of the manor.

There is also a well known pub – the Linny Inn – in what must be an old building, now much altered.  The Linny Inn, Coffinswell (June 2014).

The Linny Inn, Coffinswell (June 2014).

and an ancient church, dedicated to St Bartholomew.  The tower and churchyard of St Bartholomew’s, Coffinswell (June 2014).

The tower and churchyard of St Bartholomew’s, Coffinswell (June 2014).

The church was consecrated in 1159 and its site was chosen where the boundaries of three ancient manors met. The first building would have been built of cob walls with a thatch roof, with very small glass-less windows. It stood alone for 300 years until farm buildings grew up around it. The tower of red sandstone was built in the 13th century; its massive walls up to 9 feet thick slope inwards to eliminate the need for buttresses. The interior was extended in several stages in the 14th and 15th centuries, when larger windows with glass would have been inserted into the walls. Today the interior is surprisingly light and airy.  The interior of Coffinswell church (June 2014).

The interior of Coffinswell church (June 2014).

Because of its previous importance as a meeting place, two ancient tracks meet at the church: one from St Marychurch to the crossing point of the Teign at Hackney, the other linking Kingskerswell and onward to Totnes to the south west to tracks leading north to lower crossing points in the Teign estuary and to Shaldon. The track towards Kingskerswell, contained within hedges, can be seen here from the edge of the churchyard.  Ancient track seen from Coffinswell churchyard (June 2014).

Ancient track seen from Coffinswell churchyard (June 2014).

Haccombe

Haccombe House is situated at the end of a sheltered valley north of Coffinswell. Its date of construction appears to be uncertain – sometime between the 1770s and 1800s – and then it was significantly altered in the 1830s. The house is now divided into apartments. It is likely that there has been a dwelling of some kind on this site for a thousand years, but nothing specific is known about the earlier buildings. Soon after the Norman Conquest the land was taken from its previous owner and given to Stephen, probably a soldier in William’s army, who adopted the name of the place and became Stephen de Haccombe.

One wing of Haccombe House (August 2015)

There used to be a village along the lane leading to the church, but at some point the owner of Haccombe House ordered it to be removed as it spoilt the view, and also no doubt the approach to the house. The villagers were re-located to Netherton.

The road to Haccombe House (June 2014)

There is a small ancient church right next to the house, dedicated to St Blaise – a rather obscure saint from Armenia who was martyred in the 4th century. It was built in the 1230s by Sir Stephen de Haccombe, presumably a descendant of his Conquest namesake. This Stephen had pledged to build a church if he returned safely from the latest military expedition aimed at restoring Christian access to the Holy Land. Much later these campaigns became known as the Crusades, and ran from 1097 to 1291. Stephen had set out for points east with the Bishop of Exeter in 1228 (bishops were expected to be military as well as spiritual leaders in those days), and returned five years later.

The church of St Blaise, Haccombe (August 2015). The bell dates from 1290 and may be the oldest in Devon.

Over time the manor including the church came into the ownership of people from significant local landowning families: the Courtenays, and latterly the Carews. The church was in effect the chapel of the manor house and became a mausoleum of the lords of the manor.

There are three well preserved stone effigies dating from the late 13th century. This one of a knight clad in a suit of mail armour carrying a shield bearing the arms of the Haccombe family is thought to be of Sir Stephen de Haccombe, the founder of the church.

Detail of above, showing the Haccombe family arms on his shield and the remains of the original decoration.

The highlight of the church is generally considered to be an unusual diminutive alabaster effigy of a boy dressed in a costume from the late 14th century, which is considered to be the finest of its type in England. It is said to commemorate Edward Courtenay, who died aged 16, and closely resembles similar effigies of the children of King Edward III in Westminster Abbey.

The church floor is also worthy of note, having a fine collection of around 400 medieval tiles, with 29 different designs.

One section of the church floor. Some of the designs are depictions of coats of arms with connections to people involved with the church: here the Royal Arms of France are second from left in the third row down, and left hand side in the fourth row shows a double headed eagle, which is probably the arms of Speke of Daccombe.

And finally, there are two candle holders resembling arms protruding from the walls, which were used for candles to illuminate the altar. The church guide refers to them as ‘Vestas arms’, presumably a reference to the Roman goddess of hearth, home and family, who is associated with a sacred fire that burned at her temples. The guide claims that they are unique to Haccombe church.

One of the ‘Vestas arms’ in front of an inscribed panel next to the altar.

Ogwell

Apparently ‘Ogwell’, or several variations of it that were around when the Domesday book was compiled, could be interpreted to mean ‘The Well of Spectres’ or ‘The Well in the Cave’, but more probably ‘Wogga’s Spring’.

Today there are about 2,500 people living in East and West Ogwell together, mostly in housing built in the late 1980s and 1990s, but there are some very fine old buildings in the old village centre around the church.

Buttercombe Cottage (November 2013) was probably originally a farmhouse.

Buttercombe Cottage (November 2013) was probably originally a farmhouse.

Wedgewood Cottage, with its prominent external chimney (November 2013). According to its Heritage listing, the dramatic appearance of this building ‘forms the focal point for the village street’. It is described as ‘late medieval, altered in the late 16th century of 17th century.

Wedgewood Cottage, with its prominent external chimney (November 2013). According to its Heritage listing, the dramatic appearance of this building ‘forms the focal point for the village street’. It is described as ‘late medieval, altered in the late 16th century of 17th century.

East Ogwell church and Manor House (November 2013). The church, whose origins go back to the 13th century, was enlarged and altered in the mid 15th century.

East Ogwell church and Manor House (November 2013). The church, whose origins go back to the 13th century, was enlarged and altered in the mid 15th century.

The interior of East Ogwell church (November 2013).

The interior of East Ogwell church (November 2013).

Perhaps the most interesting thing about the church are the two pieces of ancient stone grave marker that have been built high up into the exterior walls of the nave, possibly when repairs took place during the 1880s. They are not noticeable unless you know what they are: I went back to the church to photograph them after Mr David W Thomas kindly drew my attention to their importance and provided the following explanation.

The Ogwell stone grave marker is one of those extremely rare examples of a people that pre-date the coming of the Saxons to South Devon, which was from the 7th Century onward. The two stones were originally part of a grave marker that would have stood nearly 8 feet tall. One has still legible and complete text, on the other the text has deteriorated and is incomplete, as it has been trimmed when it was inserted into the wall.

The text reads CA(-)OCI FILI (-)PLICI, that is, ‘(the stone) of Ca(-)ocus (modern Ca(-)og), son of, (-)plicus’, with FILI or FILII. The two letters missing at the beginning of the second line might be E, possibly P or R, followed perhaps by S, but it is uncertain how many letters are lost from each lacuna, the names are not fully recoverable and therefore translation remains open to debate. The name forms are Brittonic, which you can reasonably say was the local language. The -OCI of the first name appears to be South West British (up to the mid-6th century), or if later Primitive Cornish. However, the use of the horizontal I puts it somewhere in the 6th to 8th century AD therefore, more likely, it is Primitive Cornish. The Father’s name may derive from the latin Publicius. The son’s name may correspond to Old Welsh caiauc: ‘wearing a brooch’.

There is no record of where the complete pillar stone stood before the 19th Century rebuilding or even before the first Christian place of worship was erected on this site, but in either case it would not have been far. Mr Thomas concludes: ‘We can see throughout history and back into prehistory that a victorious army or a new religion always uses proven strategic or religious sites of the vanquished. So, it is without doubt in my mind that when you worship here today you are doing so on a very special site and possibly continuing a ritual tradition that goes back thousands of years.’

The Manor House, which could hardly be any closer to the church …

…. dates from the 15th century or early 16th century, but parts were rebuilt after it was left to go to ruin in the 18th century. It was originally built by the Reynell family, who had lived in East Ogwell from the late 14th century, intermarrying with prominent Devon families and as a result gradually increasing their landed wealth. At one time the Manor House was owned by Richard Reynell (1519-85) who was a courtier to King Henry VIII and bought West Ogwell from the Courtenays. One of his sons bought Forde House in Newton Abbot (q.v.)

The lane leading from East Ogwell to Denbury, close to Stubbins Cross (November 2013)

The lane leading from East Ogwell to Denbury, close to Stubbins Cross (November 2013)

Denbury was given its name by the Saxons (‘Deveneberie’) which meant ‘Fort of the Men of Devon’. During the reign of Edward the Confessor Denbury was a thriving manor owned by the Abbot of Tavistock, Aeldred (or ‘Aldred’/ ‘Ealdred’), who earlier may have been the priest of Denbury. Aeldred was on good terms with the King and became a very important person of his time, serving as a diplomat and even a military leader (against the Welsh!). After promotion to Bishop of Worcester he travelled to Germany as an ambassador to the Emperor Henry III. In 1058, on completion of the new abbey church in Gloucester that he had commissioned, he went on a pilgrimage to Jerusalem, which no English Bishop had ever done before. Soon after his return in 1061 he was promoted to Archbishop of York, and became celebrated as a great statesman-prelate who had the reputation of being able to reconcile the bitterest of enemies.

Harold Godwinson being crowned King of England, from the Bayeux Tapestry

Harold Godwinson being crowned King of England, from the Bayeux Tapestry

In 1066 Aeldred crowned Earl Harold in succession to Edward. (The above extract from the Bayeux Tapestry indicates that Archbishop Stigand of Canterbury performed the ceremony, which is a reasonable assumption by the tapestry makers working some years after the event, but it seems more likely that it was Aeldred, who was the next most senior bishop, because Stigand’s occupancy of the See of Canterbury was of doubtful legality, and Aeldred had supported Harold’s claim to the throne, and therefore was on good terms with Harold.)

Then on Christmas Day in the same year he also crowned Duke William of Normandy as King, after Harold’s death at the Battle of Hastings. (At that time Stigand was still ex-communicated by the Pope.) Although one assumes Aeldred would have been unhappy about the Normans taking over, he publicly endorsed William and kept his opinions to himself in order to maintain his position.  Looking along West Street towards Denbury Down (June 2014)

Looking along West Street towards Denbury Down (June 2014)

Denbury Down, the highest point between Dartmoor and the coast, provided Iron-age Celts with a good site for a defensive fort and accompanying settlement. Small irregular Celtic fields are still identifiable on the flanks of the Down. Denbury has been continuously occupied for at least three and maybe four thousand years. Between the Iron Age and the eleventh century, the village developed at the foot of the hill, latterly taking a Saxon formation of four roads radiating from a central cross. In 1285, King Edward I granted the town a charter to hold a weekly market and three day annual fair, but their origins are certain to be much earlier than that. Denbury became a burgh, which gave its prominent citizens or burghers some privileges and allowed trade to prosper. The ‘town’ was not large, but it held an important local position as a trading centre long before Newton Abbot developed.

Water was always a key element in choosing a site for a settlement. Denbury Down, together with several local farmsteads, had access to water via springs, wells or streams but the village site had a disadvantage, being built on limestone, which has underground aquifers and streams giving rise to springs and wells that were liable to dry up in periods of drought. Thus the supply of water was a constant issue in Denbury and cisterns were built to capture the spring water and make it accessible. This made the Cistern at the crossroads an important meeting place for the community. A mains supply was finally brought in after the Second World War, and by the 1950s the building was in need of repair and no water was taken from it after 1954. At this point there was pressure to remove it and open up the crossroads, but residents argued that it was an important historical legacy, and it was saved.  The Cistern at the centre of the village (June 2014)

The Cistern at the centre of the village (June 2014)

Some historians have speculated that the Cistern was also used as a lock-up, as small buildings of similar size and shape were used for temporary or overnight confinement of wrong-doers from medieval times up to the 19th century. But when an expert in old lock-ups came to Denbury in 2001, his conclusion was that the evidence for it being a lock-up is not conclusive. He also suggested that it was built sometime between 1750 and 1850, but other researchers think it may be much older.

Denbury Cistern probably occupies the site of the old market cross, the base of which has been moved to inside the gate to the churchyard, where it now supports a memorial to a 19th century Rector.  The base of the old market cross (June 2014)

The base of the old market cross (June 2014)

In the 19th century the Denbury Fair, held in September, was one of the highlights of year for people in South Devon, being attended by people from all classes of society and from a wide area. It was mainly an occasion for pleasure, but a good deal of business was also done, particularly in cheese..

The church dates back to the early 14th century and unusually is little altered from that time, but it is believed that a 12th century church originally occupied the same site, and the font from that earlier church has survived.  The interior of St Mary the Virgin, Denbury (June 2014).

The interior of St Mary the Virgin, Denbury (June 2014).

The font is made from red sandstone and its only decoration is a band of honeysuckle or palmetto of a Romanesque style. (This design inspired the border of the whole Millenium tapestry – see below).  The font, originally in use in the previous church building (June 2014)

The font, originally in use in the previous church building (June 2014)

One other notable feature is the original, perfectly preserved piscina.  The piscina in the church, which was used to wash the vessels used in dispensing the sacramental bread and wine.

The piscina in the church, which was used to wash the vessels used in dispensing the sacramental bread and wine.

The church tower is severely plain in style, but features an unusual diamond shaped clock with a single hand.  The church tower with its unusual clock (June 2014).

The church tower with its unusual clock (June 2014).

The churchyard has one of the grand old yew trees of Devon.

Local historians report that in the spring of 1876 a branch was torn from the trunk during a heavy gale. The sap was rising at the time, and the tree would have bled to death but for the skilful doctoring of the village farrier who closed the wound with some composition of a highly curative nature. For this service he sent a bill for half-a-crown (2s 6d) to the churchwardens. It looks in good health nearly 140 years later, so he must have done a good job!

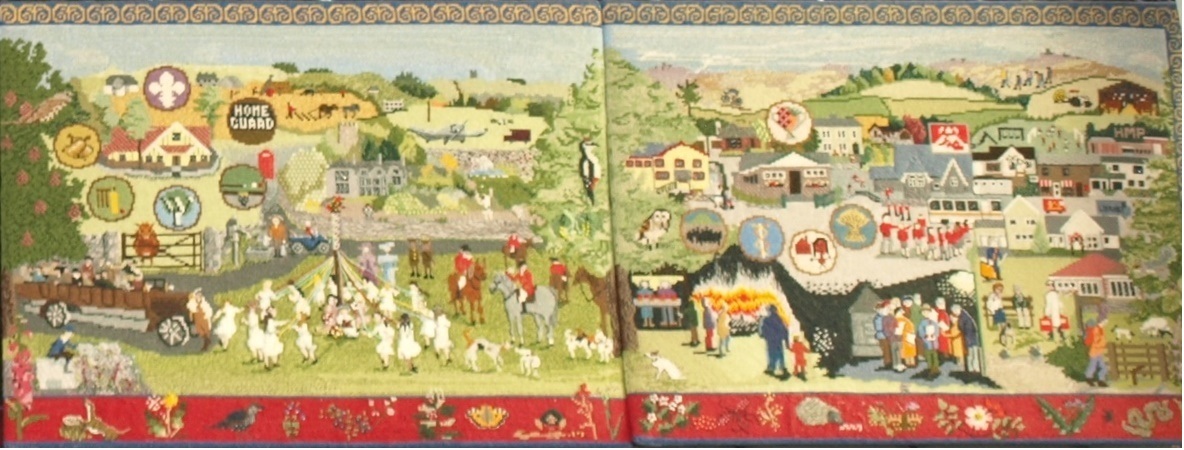

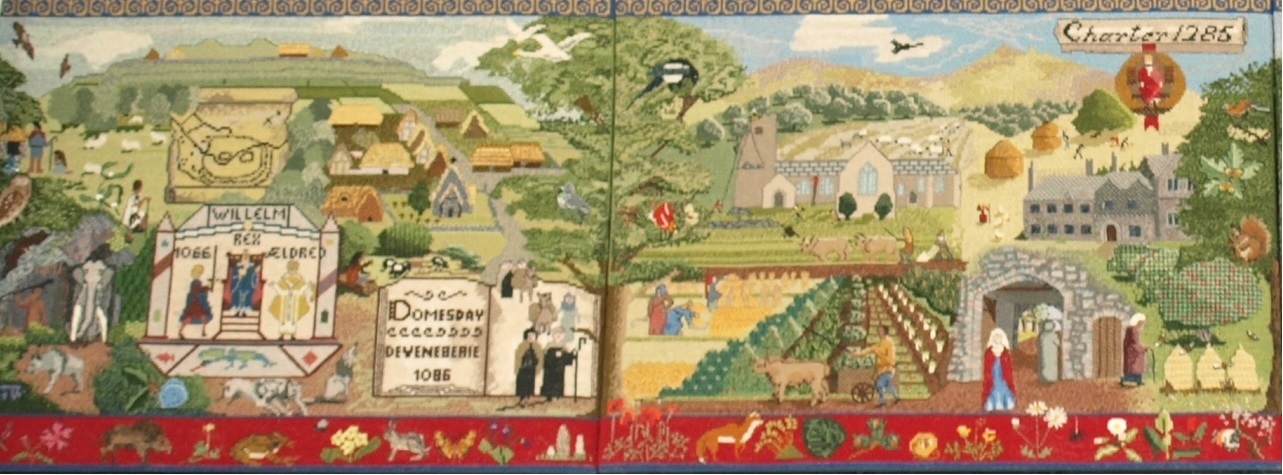

The Denbury Millenium Tapestry is attached to the front of the balcony inside the church. It was a community project and took local villagers eight years to design and make. The tapestry designers have crammed very many aspects of the history of Denbury into its seven panels.

The first panel covers the period to 1100AD. It includes elements of prehistoric life in nearby limestone caves; small Celtic fields on the hillside; two Celts praying at the Holy Well (now Halwell); visiting clergy from Tavistock, the mother abbey. The Domesday book which mentions ‘Deveneberie’ is being held by Aeldred, and he is seen crowning William the Conqueror; depicted in the same style as the crowning of King Harold in the Bayeux Tapestry.

The first and second panels of the tapestry.

The second panel gives an impression of life here in the Middle Ages. The Saxon Church was enlarged, and the yew trees which now dominate the churchyard were probably planted before the church was dedicated in 1318. The Manor house was well established by this period. Strip cultivation is shown, together with orchards and beekeeping. Denbury was a thriving medieval town, and received its first Charter from King Edward I in 1285, for a weekly Wednesday market and a three-day fair in September.

The third panel depicts activities in the period from medieval times up to the 19th century. The foreground shows the weekly market on the village green, with people selling cider, fruit, sheep, cattle, ponies, ribbons, roast meat and milk. The Union Inn was a focal point for traders and travellers, as well as local people. Denbury was still an important local centre, at one time rivalling Newton Abbot. Inside the shed is a horse driven apple crusher, as found on most Denbury farms. The wheelwright is mending a broken cart and the smith is shoeing a horse. The labourers above the lime kiln fill it with stone and coal before it can be lit and converted into lime for the fields.

The middle (fourth) panel shows the interior of the church, surrounded by two side panels with inscriptions that are to be found round the Tenor bell in the tower. Great care was taken to ensure that the dimensions of the church were accurate, and to find ways of realistically depicting the stained glass windows and slate floor.

The right hand side of the middle panel and the fifth panel.

The right hand side of the middle panel and the fifth panel.

The fifth panel depicts the annual fair which was started in the 13th century and ran until 1866, when it was stopped by the prevalence of rinderpest, an infectious disease in cattle. The scene is set in the nineteenth century. The cart in the foreground is being loaded with bales of cloth, which was woven in the village for woollen mills in Newton Abbot. In 1841 Denbury listed a great variety of tradesmen, including 33 weavers. The buildings shown include the Church House Inn, the Baptist chapel, the village school and the Rectory.

The sixth panel shows the village green in the first half of the 20th century. There are two soldiers from World War One, and traditional activities of the time including the South Devon Hunt, Maypole dancing and a charabanc outing. Also shown are a horse-drawn rake, a steam elevator, a cider crushing house, and an aeroplane – an airfield on what is now the site of Channings Wood prison was briefly active in 1935.

The right hand (seventh) panel has elements illustrating village life in the second half of the 20th century: various styles of modern village houses, the village hall, a local nursing home, a playgroup, Bonfire Night, carol singers, a tractor, the prison, and the post office, now the only shop.

North Street, with the Post Office and shop on the right, with its small red and white striped awning, as on the tapestry. (June 2014)

North Street, with the Post Office and shop on the right, with its small red and white striped awning, as on the tapestry. (June 2014)